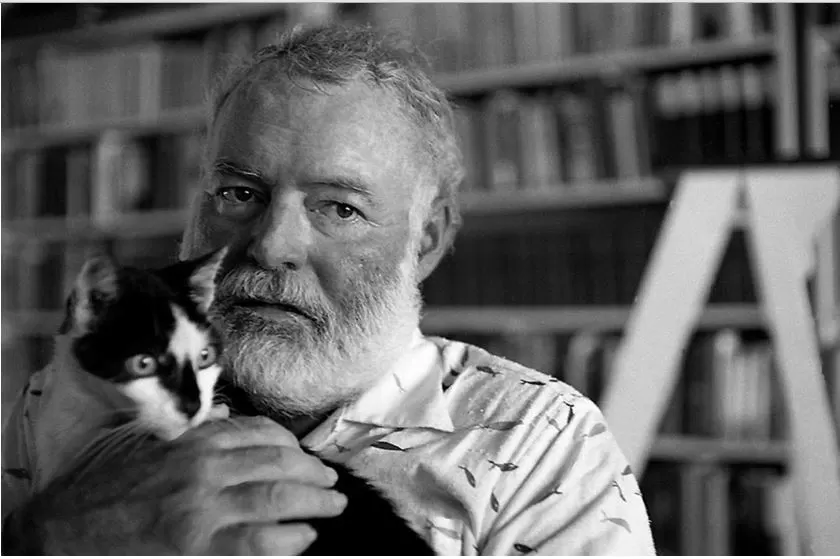

From Hemingway to Arts and Crafts

This article has been republished. Original date of publication: May 14th, 2018.

“I have a good life, but I must write because if I do not write a certain amount, I do not enjoy the rest of my life.”

That is an Ernest Hemingway quote, and while I would never compare myself to Hemingway, I can appreciate both his desire and his need to write each day. Hemingway is best known for his fiction, both short stories for magazines (which paid the bills) and his novels, which paid far less but which garnered him the 1954 Nobel Prize For Literature for “mastering the art of narrative,” as well as securing his place in 20th century literature.

While Hemingway relied on his steady stream of personal real-life adventures, from African safaris to serving on the front lines of World War I, in contrast I rely on research.

And I love research even more than I do writing.

My current work in progress is a study of an Arts and Crafts cottage industry, aptly called Biltmore Estate Industries, here in Asheville. From 1905 until 1917 it remained adjacent to the 146,000-acre Biltmore Estate, whose owner, George Vanderbilt, also financially supported Biltmore Estate Industries. The young men and women who worked there produced carved walnut bowls, trays, picture frames, and custom-made furniture for both tourists and area residents, including Edith and George Vanderbilt.

A few weeks ago the curatorial staff invited me to go behind-the-scenes at George Vanderbilt’s 250-room mansion, inspecting a wide variety of pieces they had divided into three categories under the Biltmore Estate Industries umbrella: signed, unsigned but attributed, and unsigned but hopeful.

We had a fantastic morning, slipping behind velvet ropes and picking up, with gloved hands, pieces we were inspecting, much to the amazement of the steady stream of tourists gawking at us from the doorways. By the time we were finished we had traveled from one end of the mansion to the other, from servant’s quarters in the basement to towering guest bedrooms offering panoramic views over the lush French Broad River valley.

As is often the case, nearly all of their “unsigned but hopeful” pieces turned out to be similar to what was made at Biltmore Estate Industries, but not. Several of their “unsigned but attributed” ended up becoming “unattributed,” but, in my opinion, may have come from some smaller, lesser known woodworking enterprises located in Western North Carolina.

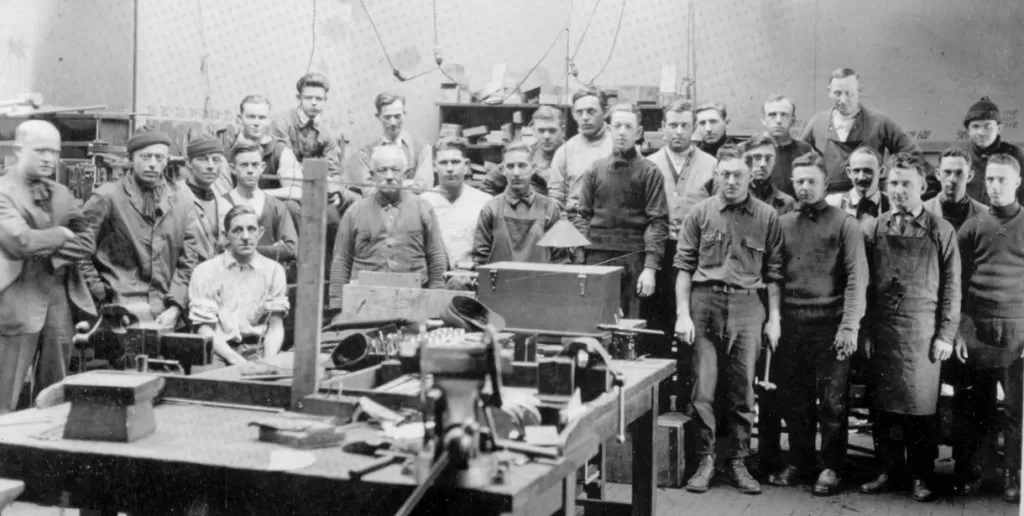

And, as I have often pointed out, in the Roycroft Shops in East Aurora, NY, (below) Elbert Hubbard would permit his coppersmiths and woodworkers to make pieces to take home for themselves or to give as gifts, but they could not bear the Roycroft stamp. The same could easily have happened at Biltmore Estate Industries and other Arts and Crafts shops across the country.

Which is yet another reason why we should never be so focused on shopmarks that we forget to study and learn the design and construction techniques that are as much a fingerprint of a firm as is any paper label, brand, or metal tag.

Until next week,

“Don’t turn one mistake into two.” – Coach Battershell (my high school basketball coach)

Bruce Johnson

Photo of Ernest Hemingway and his cat courtesy of OpenCulture.com.