Paying Homage to the Women of Biltmore Industries

by Bruce Johnson

(Publisher’s note: this article has been re-published in honor of Women’s History month. Original date of publication: March 19th, 2019. The book is now available for purchase online HERE)

After last week’s lament about the challenge of marketing and selling a self-published book, the obvious question arose: why bother to write a book only a handful of people will read?

Trust me, I ponder that question daily.

Especially when there are so many other projects awaiting my time and energy, all of which hold more promise of ever showing a profit.

A profit.

(“Ay, there’s the rub,” chuckled Hamlet at him from the wings.)

As I mentioned last week, writing, whether it involves books, columns, articles, catalogues, or websites, has always been a part of my life, but writing alone has never had to pay the bills. I can state, however, that all of my books have at least paid for the cost of their printing. But no writer ever wants to accurately calculate the number of hours invested in tracking down obscure leads, reading earlier reference books, locating missing quotes, and confirming questionable sources of information.

People in every field, from attorneys and accountants to veterinarians and physicians, do pro bono work, as do all historians. The only difference is most of their clients are alive.

Mine aren’t.

My historical books have delved into the lives of silversmith William Waldo Dodge, artist Grant Wood, authors Thomas Wolfe and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Arts and Crafts pioneers Gustav Stickley, Elbert Hubbard, and Frank Lloyd Wright, and entrepreneurs Edwin Wiley Grove and Frederick Loring Seely, the designers of the historic 1913 Grove Park Inn.

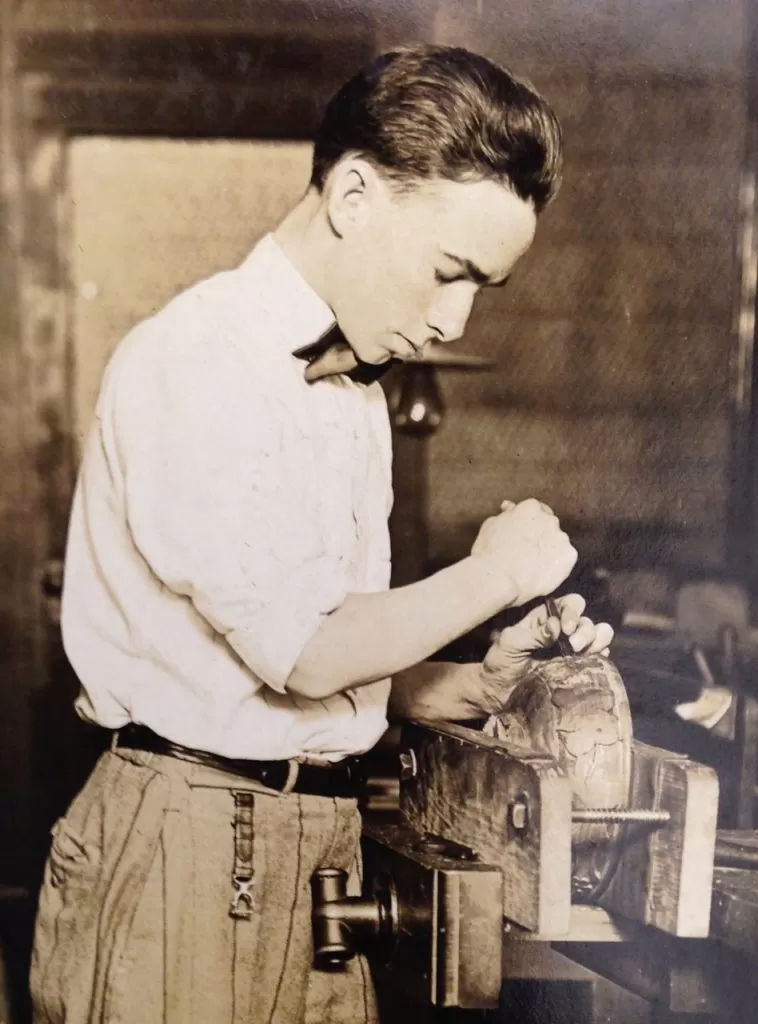

My next subjects are two modest Arts and Crafts era women, Eleanor Vance and Charlotte Yale, who arrived in Asheville in 1901. Four years later, with the financial support of George and Edith Vanderbilt, they had transformed a group of curious teenage boys and girls into Biltmore Estate Industries, an Arts and Crafts cottage industry soon noted for its fine carved furniture, bellows, trays, picture frames, hearth brushes, and more.

I first encountered examples of their work when I moved to Asheville in 1988, the inaugural year of the National Arts and Crafts Conference at the Grove Park Inn. Like many others, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Instead of oak, they preferred walnut. Rather than letting the grain of the wood serve as the only decoration, as Gustav Stickley had decreed, they hand-carved native dogwood blossoms, grape vines, and oak leaves around their bellows, trays, and frames.

Did that disqualify it for consideration as being “Arts and Crafts?”

It took me a while to diagnose my own severe case of tunnel vision, but eventually it sunk in: these talented men and women wielding their chisels and gouges as skillfully as a trained surgeon were more representative of the Arts and Crafts philosophy of handcraftsmanship inspired by nature than the famous factory owners to whom we pay homage.

And so I am digging through sales records, studying early catalogues, searching for elusive correspondence, and even visiting the forgotten gravesites of Eleanor Vance and Charlotte Yale in Tryon, NC, where they retired and where they died in 1954 and 1958.

No one took much notice when they passed away, nor since. They died without heirs or money. They never paid much attention to working for a profit, just the satisfaction in teaching young men and women how to use their hands, head, and heart to earn a living and to take pride at the end of each day in what they had accomplished.

Until next week,

“If you are going to do something, do it right.” – William Albert Johnson, my father

Bruce

PS – If you ever come across an example of their work bearing the FORWARD arrow or the name Biltmore Industries, I would appreciate seeing a photograph of it for my research. Thanks!