Head, Heart and Hand

Editor’s note: this article has been republished. Original date of publication: October 22nd, 2019.

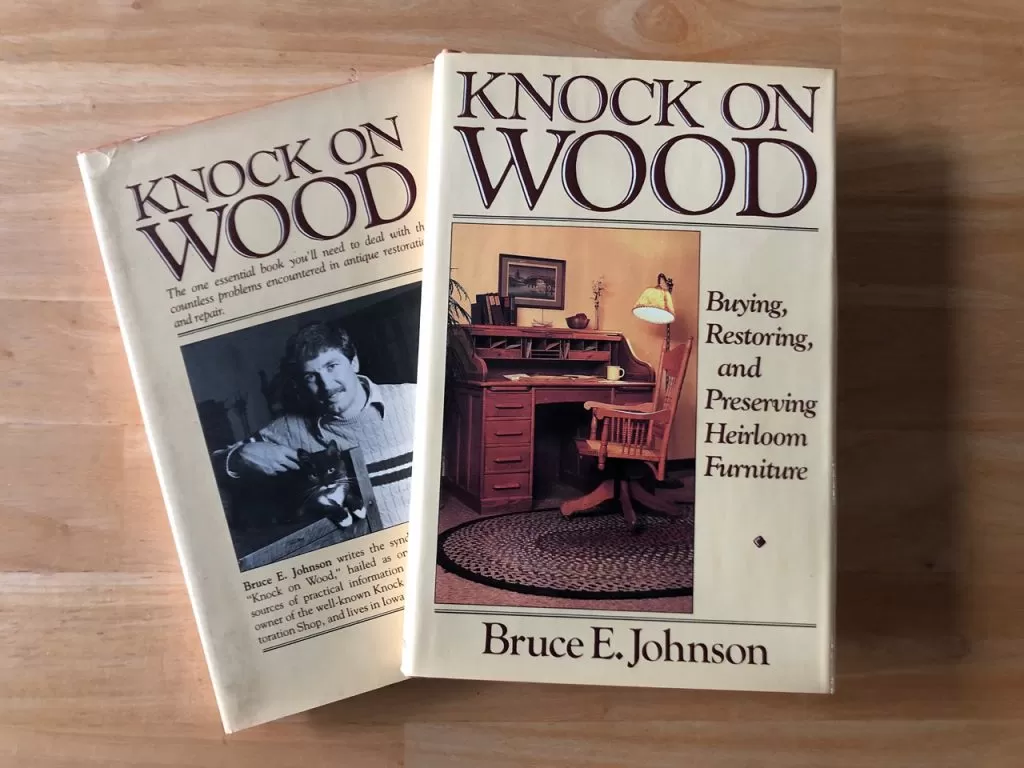

The first business I started after serving for five years in a high school classroom was an antique restoration shop in Iowa City. I named it Knock On Wood, drawing upon the Greek myth that if you knocked on an oak tree, Zeus would watch over you. And this former English major needed all the help I could get, because I had spent my college years analyzing Keats and Kerouac rather than a balance sheet.

Antique restoration also required woodworking skills necessary to duplicate missing or broken rungs, spindles, leaves, and rockers. Much of what I needed to know I learned through trial and error, with plenty of errors, many of which I included in my first book, named after my shop.

That shop was in a century old linseed oil factory beside a creek just south of the downtown district. At that time Golden Oak was the rage, and my business grew on the popularity of oak curved-glass secretaries, fancy sideboards, beds with six-foot headboards, and pressed-back chairs. None had been particularly well made in the 1890s, so I was kept busy regluing chairs, turning spindles on a lathe, and patching thin veneer.

A few years later customers also began bringing in examples of Mission Oak, which we now correctly call Arts and Crafts. Soon, I was selling my Golden Oak furniture and replacing it with Arts and Crafts. As I did I began reading about Gustav Stickley and his early businesses, from making furniture beside his teenage brothers to opening his own Arts and Crafts workshop in 1900 in an old factory by the Seneca River near Syracuse, New York.

Fast forward thirty-some years later and I am standing this past weekend in my garage workshop, making a pair of oak tabourets based on Gustav Stickley’s design. Just as he and his small band of workers did, I created plywood patterns for the arched stretchers, drilled holes for the figure-8 fasteners in the tops of the legs, and beveled the bottoms to prevent them from splintering when dragged across the floor, just as Gus did.

Whenever possible, they used machinery to speed the process: power saws, planers, and sanders, and so do I. But there comes a point in the fitting and assembly that machines remain quiet. Regardless whether it was 1901 or 2019, at that stage the craftsman and each part develop a relationship, as each board is thoroughly inspected, selecting the best grain to face outward. Each clamp is carefully tightened. Too loose and the joint will fail; too tight and too much essential glue will be forced out.

Today, just as it was then, dyes and stains are tested on scraps of wood, then rubbed on. Finishes are brushed out, allowed to dry, then buffed smooth. All by hand. Finally, when approved by the foreman, a small red decal or paper label was then attached before the piece left the workshop, destined for a new bungalow for a young couple in a suburb of Omaha, St. Louis, Portland, or San Diego.

I am sure a potter, a coppersmith, an embroiderer, or a printmaker would tell you the same thing and here it is. If you try your hand at making just one piece, you will come away with an even greater appreciation for those objects we love so much that we don’t collect them, we live with them.

Until next week,

“The product of the head, heart and hand is a thing to be loved.” – Elbert Hubbard

Bruce