A Shopmark for the Holidays

By Bruce Johnson

Editorial note: This article has been re-published. Original date of publication: December 24, 2019.

When I was a high school English teacher back in Illinois, I spent more of my free periods in the woodshop with a table saw than in the library with William Wordsworth. My principal, in fact, once suggested that perhaps I should reconsider my career choice.

Five years later, I opened Knock On Wood Antique Repair & Restoration, which was a combination refinishing and woodworking business. I had one employee. Ironically, seven years later, he also suggested that I should reconsider my career choice, as I was spending more time writing than tending to business. He gave me an option: either sell him my business or he was going to become my competitor.

That was an easy decision.

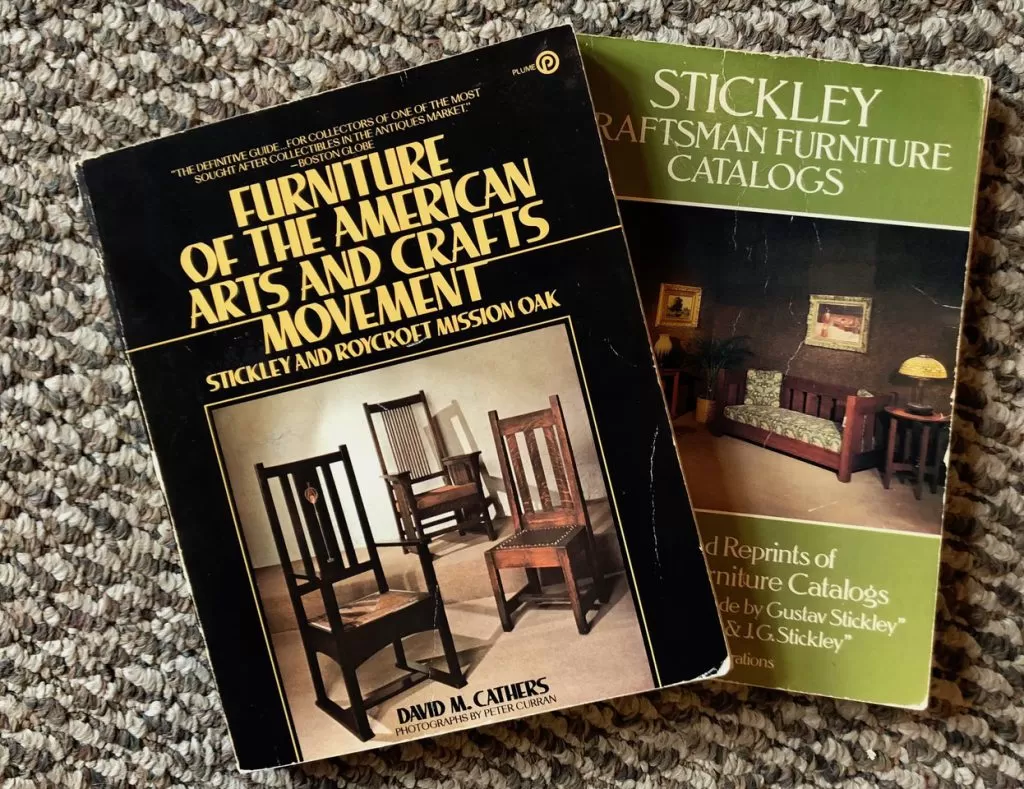

It was about that same time that I discovered Arts and Crafts, and had begun scouring Midwest antique shops and auctions for anything brown, pegged, and heavy, especially if it came with a faded decal inside a drawer or a paper label on the back. I nearly wore out two copies of David Cathers’ book, Furniture of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, one of which always stayed in my Ford Econoline van, along with a road atlas and a stack of quilted packing blankets.

David and others taught me a great deal about furniture shopmarks, from where to look for them to recognizing a faded fragment or a shadow where one had been. Initially, I could never understand how someone could make a piece of furniture and let it go out the door without a shopmark, so whenever I had a commission to make a custom piece of furniture, I attached to it one of the small brass plates I had ordered.

Since turning Knock On Wood over to my assistant back in 1985, I have only made furniture for myself and as gifts to friends and family. Those projects, to their relief, are invariably small like tabourets, footstools, and table lamps. This past month, I was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright to make a pair of mid-century, walnut and hard maple end tables for each of my adult sons. As I was rubbing out the final finish with #0000 steel wool and a burnishing cream, I realized I hadn’t signed them. My first reaction was predictable: these weren’t major pieces, and they were going directly to my sons, so the tables didn’t need a shopmark.

But then I thought about all of the Arts and Crafts pieces, some just as modest as my end tables, that I had turned over and upside down, hoping to find some clue as to who had made them and when. So I dug around in my workshop and found one of the brass plaques I had been using back in the 1970s, and stuck it on the underside of one table. For the other, I simply turned it over and used a felt-tipped pen to sign and date it.

And as I did, I was again reminded as to how and why so many pieces of antique furniture left their workshops without a shopmark. Or how a particular shopmark we historians deem “early” in a woodworker’s career could appear on a piece of furniture he or she had made several years later.

And why David Cathers taught us so many years ago that a shopmark, when it appears, should simply confirm what the unique construction techniques and the design details inherent in the piece — its figurative fingerprint — had already told us about who made it.

Until next week,

“Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” – Pablo Picasso

Bruce