The Dangers of Tunnel Vision

There have been times in my life when I have been more focused than a laboratory microscope on my collecting. So focused, in fact, that I have literally stood blindly by as something even more important crossed my line of vision.

The first time was in 1962, when my grandmother picked me up one Saturday morning in her new Chrysler Imperial to accompany her to a select list of yard sales she had clipped from the classified ads. Each had been scrutinized, analyzed, selected, and Scotch-taped to notecards, organized in order of most promising to least promising, based not only on the description of the goods for sale, but also on the address.

(“That’s a good section of town. Lots of rich people live over there.”)

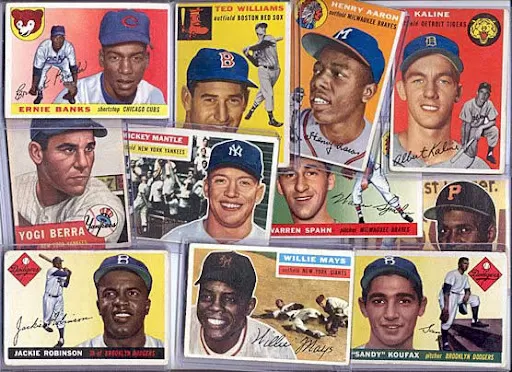

She preferred moving sales, explaining to me that those people are more motivated to sell items they would otherwise have to pay professional movers by the pound to transport. On this bright Saturday morning, the family was also selling their grown son’s baseball card collection, one which filled several shoeboxes, each neatly organized by teams, from the Milwaukee Braves and the Philadelphia Phillies to the Chicago White Sox and my personal favorite, the New York Yankees.

I was so awestruck by his collection of my Yankee heroes – Whitey Ford, Yogi Berra, Moose Skowron, Bobby Richardson, and, of course, Micky Mantle and Roger Maris – that I declined their generous offer to take the entire collection. I gleefully walked away with a handful of Yankee cards, leaving behind Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Sandy Kofax, Don Drysdale, and other valuable cards, even as I recognized that puzzled look of disappointment on my grandmother’s face.

You would have thought I would have learned from that youthful mistake, but not so. In the late 1980s, as I was learning about the historic 1913 Grove Park and its unsurpassed collection of rare Roycroft furniture, I more than once wished that it had been Gustav Stickley rather than Elbert Hubbard who had secured the contract to furnish the resort hotel.

Just as bad, in the years which followed I came across the work of two Asheville firms active during the Arts and Crafts era, and again failed to recognize the limitations of my acute case of tunnel vision, also leaving them behind.

“Gustav Stickley rejected hand carving,” I reasoned, “so how can a workshop of woodcarvers decorating lathe-turned walnut bowls with dogwood blossoms, oak leaves, and acorns be considered Arts and Crafts?”

“And how could a self-taught potter working by himself in a shack outside Asheville, digging his own clay, grinding his own glazes, turning his own vases, and hand-decorating them with Western scenes of covered wagons, pioneers, mountains, and pine trees be classified alongside Rookwood, Grueby, or Van Briggle pottery?”

So, while I now appreciate and also collect the work of Biltmore Industries and Pisgah Forest Pottery, I cannot help but wonder about the many great examples I passed by without so much as a second glance, as I was racing about looking for my next piece of Stickley furniture or Roycroft metalware.

The consequences of a severe case of acute tunnel vision . . . .

Until next week,

“Our greatest regrets are the ones we let get away.”

Bruce