Dueling Divas

Traveling from North Carolina to Illinois recently gave me the opportunity to spend a couple of hours in the Cincinnati Art Museum, where I immediately headed to the permanent display of Rookwood Pottery.

During the latter years of the 19th century, Cincinnati residents followed newspaper reports tracking a public rivalry between two of the city’s most illustrious societal figures: Mary Louise McLaughlin (1847-1939) and Maria Longworth Nichols Storer (1849-1932).

Born into a wealthy Cincinnati family, 27-year-old Louise McLaughlin enrolled in a china painting class taught in 1874 by Englishman Benn Pitman. Students were provided with blank porcelain plaques, plates, cups, and saucers which had been kiln-fired to a bisque hardness. Using their own designs or those provided by their instructors or available for purchase, the ladies would paint decorative floral motifs or even portraits on their wares before they were fired a second time to bond the paints to the porcelain.

Louise McLaughlin studied the techniques of the craft, experimenting with means of streamlining the process. In 1877, her efforts were met with widespread publicity with the publication of her book, “China Painting: A Practical Manual For the Use of Amateurs in the Decoration of Hard Porcelain.”

One individual, however, who was not smitten with McLaughlin’s rapid rise was Marie Longworth Nichols. Prior to McLaughlin’s introduction to china painting, the 24-year-old Nichols had already displayed examples of her own china painting at the school, some of which had inspired McLaughlin to take up the craft. At subsequent Cincinnati exhibitions, the decorated porcelains of both women were displayed side-by-side, prompting critical comparisons and spurring a growing and very public rivalry between the two ambitious young women.

Like other decorators of the time, both Nichols’ and McLaughlin’s designs were painted on top of the porcelain glaze, leaving them susceptible to any abrasions. In Europe, a scant few commercial potteries had been able to decipher the secret to under-glaze decoration, wherein a clear glaze could be formulated to adhere atop the painted decoration during the final firing, thus preserving and protecting the decoration beneath a clear film. Determined to join their ranks, in 1878 — after months of experimenting — Louise McLaughlin became the first American to achieve success with an under-glaze decoration. Her efforts were soon met with world-wide acclaim, awards, and recognition from everyone – with the exception of her rival Maria Longworth Nichols.

To showcase her success with under-glaze decoration, McLaughlin undertook the creation of the world’s largest under-glaze decorated vase. In 1880 she dubbed it the “Ali Baba Vase,” as it stood more than 37 inches high. She later donated it to the Cincinnati Art Museum, further securing McLaughlin’s position atop the art pottery world.

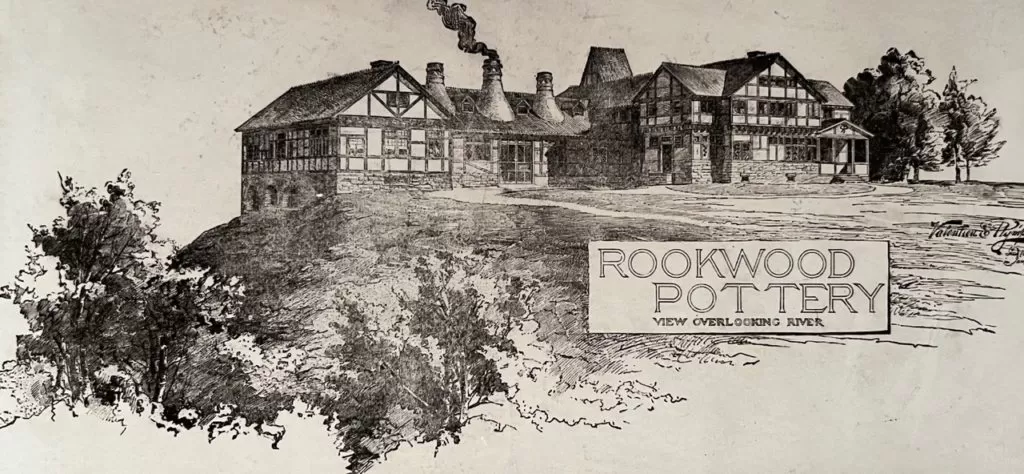

In response in 1880, Maria Longworth Nichols approached her father, Joseph H. Longworth, one of the wealthiest men in Cincinnati, requesting that he fund her new business venture she called the Rookwood Pottery Company. Perched atop a towering bluff overlooking the Ohio River, the state-of-the-art pottery and its growing staff soon undertook Nichols’ pet project: creating an under-glaze vase even larger than that of Louise McLaughlin’s.

Decorated with swirling fish painted by artist Albert Robert Valentine, the “Aladdin Vase” was unveiled in 1883. Although it stood seven inches shorter than her rival’s vase, the Rookwood vase was larger in diameter, considered a more challenging accomplishment on the potter’s wheel.

In later years, Louise McLaughlin gradually slipped from public view, spending her time writing books and creating art pottery for herself. In contrast, under Marie Longworth Nichols’ direction, Rookwood Pottery rapidly built a world-wide reputation by utilizing and perfecting the under-glaze formula first developed and publicized by her rival McLaughlin.

In 1885, Marie Longworth Nichols’ husband died; the following March she married Bellamy Storer, a successful Cincinnati lawyer who was soon elected to Congress and later became an ambassador to Belgium and Spain. Given her new responsibilities, in 1889 Marie Longworth Nichols Storer made the decision to turn Rookwood Pottery over to her manager William W. Taylor.

Today the two monumental vases – Louise McLaughlin’s “Ali Baba” and Marie Longworth Nichols Storer’s “Aladdin” – stand side-by-side in the Cincinnati Art Museum, illustrating the story of their creators’ rivalry and subsequent establishment of the foundation for the American art pottery movement.

Until next week,

“Rivalry adds so much to the charms of one’s conquests” – Louisa May Alcott

Bruce