My Two Adopted Aunts

It has often been said that you can choose your friends, but you can’t choose your relatives. A few years ago, however, I chose two of mine: my now adopted aunts Eleanor Vance and Charlotte Yale.

I never had the opportunity to meet either of them, as they had passed away while I was still in grade school. The closest I came was on a rainy afternoon in March when I drove from Asheville down to Tryon in search of their gravestone in the old town cemetery. The weeds behind it were nearly as high as their modest granite headstone, devoid of any personal inscription, but adorned with a carved brooch they had personally designed around two eternal dogwood blossoms.

The granite face was nearly black, stained with mold, mildew, and tannin leaching from the wet leaves of a shadowing oak tree. Unsure whom to ask, I came back the next morning at dawn, fearful of being stopped by the local police, armed with rags, scrub brushes, bleach, and jugs of water, determined to rescue their names and dates for all to see – wondering, though, if anyone would bother to look.

Eleanor Vance and Charlotte Yale had both died without children, although they had served as surrogate parents for hundreds of young boys and girls in Asheville, Biltmore Village, and Tryon. Their funerals were modest affairs, barely acknowledged in the local newspapers, for they had always sought, in Charlotte’s own words, “to serve unnoticed and to work unseen.”

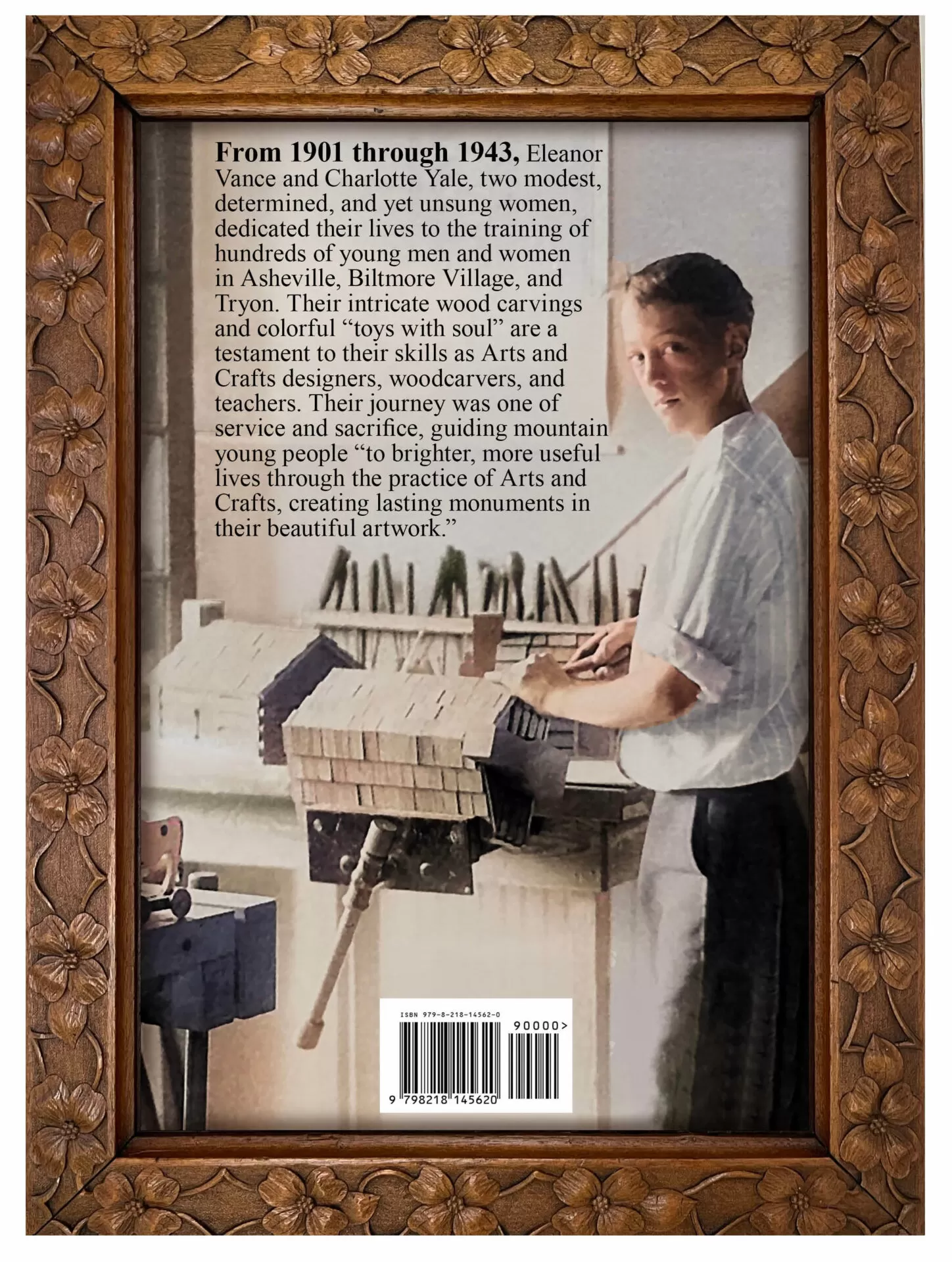

From 1901 through 1943, they taught and trained hundreds of young men and women to cut, construct, and carve oak, mahogany, and walnut bowls, trays, hearth brushes, frames, and furniture. They subscribed to Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman magazine, even making a tea table following his plans.

Just as she had been trained at the Cincinnati Art Academy, Eleanor Vance taught her eager woodworkers to turn to nature for their inspiration, decorating their hand-carved bowls with dogwood leaves and blossoms, trailing grape vines, and oak leaves and acorns. She and Charlotte Yale held them to the highest standards, vetting every piece before it could bear their branded shopmark: the word “Forward” inside a furled banner, generally over “Biltmore, N.C.”

Early in my personal Arts and Crafts career, I know I passed by fabulous examples of their work, as I suffered from a severe case of tunnel vision: if it wasn’t oak, fumed, and pegged, I wasn’t interested. Only later, perhaps awakened by the carved works of Charles Rohlfs, did I realize that these hand-cut, hand-carved bowls, trays, frames, and furniture adhered even more closely to the Arts and Crafts tenets espoused by John Ruskin and William Morris than did the factory-produced furniture of any of the Stickley’s.

Hopefully, I have offered my sincere apologies to Eleanor Vance, Charlotte Yale, and their talented proteges as best I could, by documenting their lives, their works, and their influence in the form of a book and a Facebook page found by clicking here.