Bringing a Shop Project Back to Life

by Bruce Johnson

Kate and I have recently been discussing the plight of the traditional, free-standing antiques shops, many of whom have been victimized by skyrocketing rents or are suffering from a younger, unappreciative clientele. What are loosely called “antiques malls” have tried to fill the void, but to survive their owners have permitted vendors to fill their booths with a jumble of country crafts and reproductions.

Despite the inevitable disappointment which follows, I still find myself pulling off the road to check out a new mall or group shop. Not long ago I was in Tryon, NC, at an architectural salvage warehouse which also stocks an often bizarre assortment of antiques, many of which I suspect were bought as part of a package deal. When I do, I tend to look for anything with a waterfowl theme, as I love to watch the ducks and geese skimming over nearby Lake Lure.

On this particular day I spotted this pair of faded ducks bursting out of a stand of cattails, another of my favorite subjects. While they didn’t make my heart skip a beat, I was intrigued by them, in part because from a distance I could not tell what they were made from. Once I picked up the frame, I could tell that the two ducks were carved from a thick piece of leather. Closer inspection revealed that these two ducks were not the work of a highly skilled Roycroft craftsman nor had they been they stamped out in a factory.

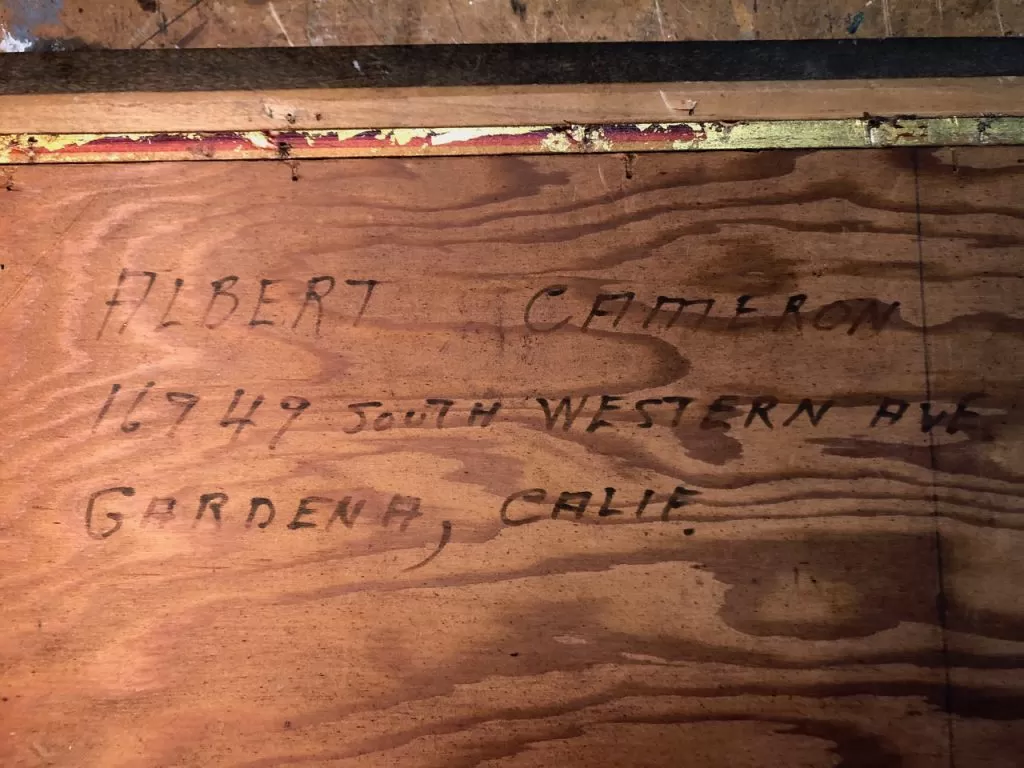

As soon as I flipped the frame over I knew what I was holding: a manual arts class project. There on the plywood backing the aspiring leather artisan had printed his name: “Albert Cameron, 16949 South Western Avenue, Gardena, Calif.” I wish Albert had included the year, but that was not to be found. What I suspect is that Albert most likely selected a pattern drawn by a professional artist and used carbon paper or some other means to trace the design onto the leather, which he then carved using an assortment of knives and punches.

The leather was dry, the color bleached out, and a couple of deep scratches were permanently imbedded in it, but I wasn’t about to leave Albert’s shop project languishing any longer in the old warehouse. I paid the tagged $48 without haggling and brought it home to my workshop.

Once he had finished the final tooling and stamping, Albert had brushed on a coat of finish, leaving behind several brush marks, which I decided to leave rather than risk damaging the leather trying to remove them. After cleaning it with a soft rag dampened with mineral spirits, I applied a coat of dark paste wax to add some color to the recessed areas and to protect the leather.

The paste wax did not transform Albert’s shop project into a masterpiece, but it did bring his two ducks and the stand of cattails back to life. As I expected, the dark wax lodged in the recesses of his carving, revealing just how painstaking it must have been for Albert to carefully cut, stamp, and carve each layer of feathers in his two ducks – not to mention all of the detailing in the stand of cattails.

I saw no reason to replace the frame Albert had picked out and certainly would never discard the plywood backing bearing his name and address, so once the wax had dried and I had buffed it to a satin sheen, I found a suitable place for his artwork in our home. There it reminds me daily that not all Arts and Crafts bears a shopmark from a famous maker or firm.

And some would say, quite correctly, that Albert Cameron’s hand-carved ducks and cattails are even more loyal to the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement than the factory-made furniture, art pottery, and metalware we admire.

– Bruce Johnson