Clara Barck Welles: Founder of the Kalo Shop, Suffragette and The 20th Century’s “New Woman”

by Kate Nixon

Portrait of Clara Barck Welles, 1906, founder of The Kalo Shop in Chicago.

When considering the wide array of influential women in the Arts and Crafts movement, it’s not difficult to see the value that Clara Barck Welles brought to the table. Entrepreneur, silversmith, teacher, independently minded and an important element of the growing Suffragette group of Chicago, Clara was a business owner ahead of her time who, by encouraging five other women to join her, created one of the best silversmithing firms of the Arts and Crafts era.

Clara was born in Ellenville, New York in a family that would have six daughters to a Finnish immigrant shoemaker Johannes Barck and his wife Margaret, a Swiss emigrant. Clara would be the fourth of those six daughters. The family would move across the country from New York to a farm in Oregon City. Clara and her family had no choice but to take on more responsibility after her father’s untimely death; the Barck women of the family would have to take over managing the farm. Taking on new responsibilities within the family however would serve her in developing her work ethics. Upon coming of age, Clara first worked as a weaver in the woolen mill at the Oregon City Manufacturing Co. After taking a college business course and worked in bookkeeping and sales in Portland and in San Francisco, Clara would gain her business savvy experience before entering the School of Art Institute of Chicago, where she would meet five other women who would help her form the Kalo Shop.

Metalsmiths, jewelers, designers and crafts workers seated in front of the Kalo Arts Crafts Community House in Park Ridge, IL, c.1910. Image courtesy of WIkimedia Commons.

Clara standing in front of her South Michigan Avenue Kalo Shop store in 1937.

Origins of The Kalo Shop

The Kalo shop opened in September 1900 at 175 Dearborn St. in Chicago, IL with the help of fellow graduates from the department of Decorative Design at the School of the Art Institute. Clara dubbed her new venture the Kalo Shop from the Greek word for “beautiful” – an appropriate use given the luxurious look of her silver products. Before her group dabbled in silver, Clara’s early Kalo Shop at first made goods from burnt leather and goods through weaving. After marrying metalworker George Welles, her interest changed to jewelry and metalware. Clara and her fellow graduates who assisted her in her new business venture gradually became known as “the Kalo Girls” and by 1908, Clara’s idea of The Kalo Shop would gain new grounds and inspire many others.

Clara and her husband George established the Kalo Art-Craft community in their Park Ridge residence to supply works for a larger shop. They eventually accomplished their goal in the Fine Art Building on Michigan Avenue. Initially, the Kalo girls were the only workers, but soon expanded to up to 25 silversmiths. Inside their workshop, Clara and the Kalo girls would teach the craft to both male and female artists since she was an advocate of actively training women for self sufficiency. Clara would teach her artists jewelry, copper bowls and desk accessories, gradually expanding to silver tableware; her silver items eventually became the shop’s standard products with their geometric design with some pieces even featuring a C.R. Ashbee style of stone adornment. However, Clara’s work soon morphed into round and soft curves, which became the traditional design of The Kalo Shop. Clara’s designs were also locally influenced by Chicago’s own burgeoning Prairie style.

Clara as a teacher and leader

The Kalo Shop was not only a firm that would create some of the best Arts & Crafts silver ever made, it would become a schoolhouse and a workshop where creatives could flourish. In the book Chicago Metalsmithing, author and Decorative Arts curator Sharon Darling revealed Welles as a leader of metalworking and inclusivity in the workplace. Metalworking was the profession and “in accordance with the Arts and Crafts philosophy, Clara Welles devoted as much attention to her workers as to their products…she inspired others to excel in their craftsmanship…As word of her activity spread, trained silversmiths from Scandinavia regularly approached Clara Welles for work.” (Darling, p. 45, 53) The Kalo Shop would cement the reputation of her craft school by organizing exhibitions; meanwhile her business was one of the largest businesses in the area with over 50 employees.

Clara Welles (middle) in Chicago, preparing to leave for the Suffrage March in Washington, D.C., March 1913. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1910, Clara’s influence would gain new ground as the growing women’s suffrage cause made Clara into a Suffragette. Clara joined the Chicago Political Equity League, elected chair of the Park Ridge Improvement Association, and headed the Parade committee for the Illinois Delegation in the Votes for Women Procession in Washington D.C. – all in the space of three years. The following year in 1914, Clara hosted a fundraising event for the cause in her Kalo Shop with a group of 100 of society’s finest.

It was no surprise that the Kalo Shop’s motto would be “Beautiful, Useful & Enduring”; Clara had managed to keep with the Arts & Crafts philosophy of keeping items handmade using hammers of all shapes and sizes and sheets of heavy silver making custom-designed flatware that had clientele growing as well as the doors of the newly made South Michigan Avenue office revolve with many out-of-town customers. The acclaim for Clara raised to an all-time high when she was invited by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to submit representative works for an exhibition of contemporary design among other silversmiths. Her works were received as “emphatically American” and “freshly creative.” (Darling, p. 55)

The First Museum Exhibition Centered on The Kalo Shop

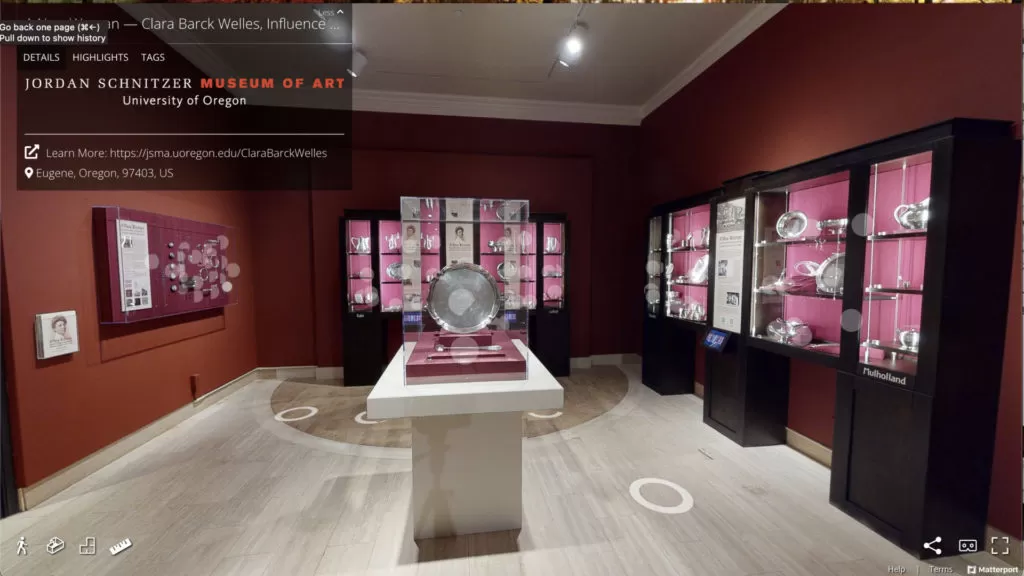

A screenshot of the virtual (Matterport) tour of A New Woman — Clara Barck Welles, Inspiration & Influence in Arts & Crafts Silver.

On October 9th, 2021, on the grounds of the The University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, the first museum exhibit centered on The Kalo Shop opened to the public revealing Welles and her journey to create The Kalo Shop legacy. The exhibit currently consists of the combined works of The University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, the Portland Art Museum and rarely seen works from private collections and will reveal the life, catalog, and social activism of Clara Welles. The exhibit will be on display through October 2nd, 2022; afterwards the exhibit will be open to touring through contacting the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art.

The Matterport virtual tour of the exhibit is also available to view through the museum’s press release page. Click here to view the virtual tour.