Marblehead: A Classic Arts & Crafts Pottery

The following passages are from the publication The Official Price Guide to American Arts and Crafts, Third Ed. by David Rago and Bruce Johnson and has been published with permission from author Bruce Johnson.

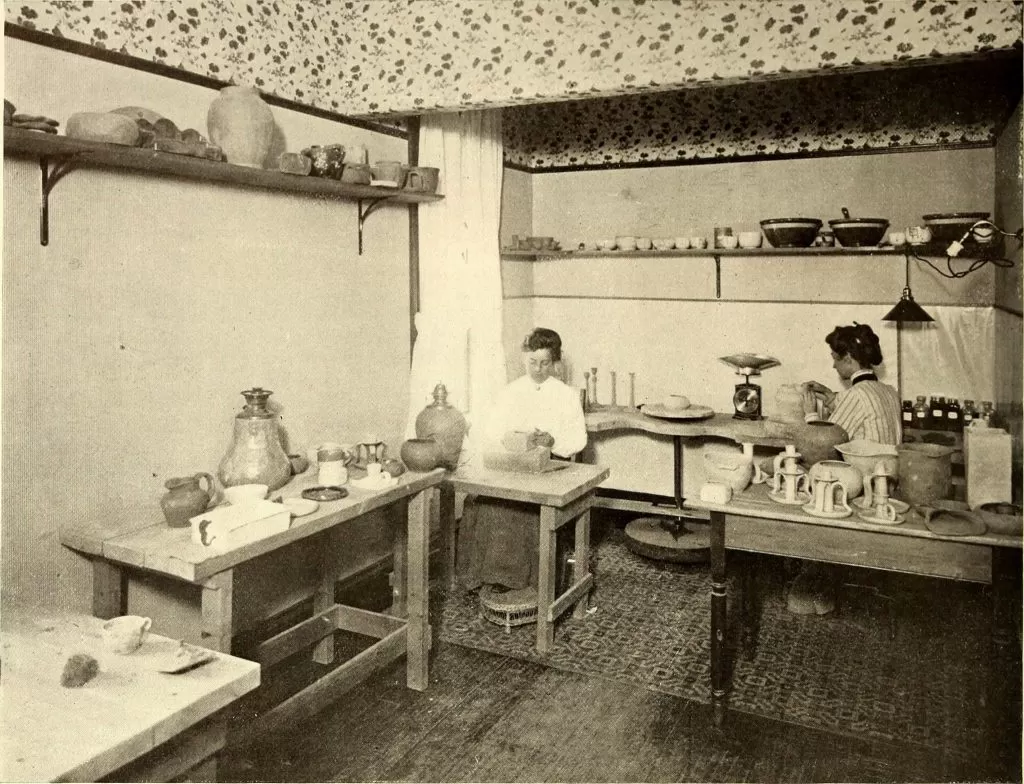

Artisans making their works at Marblehead Pottery. Image from the 1905 publication American Homes And Gardens, page 303. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Shopmarks: Impressed outline of a ship and the initials MP; all enclosed in a circle, occasionally with initials A.E.B. (Arthur E. Baggs) and/or H.T. (Hanna Tutt)

Shopmarks: Impressed outline of a ship and the initials MP; all enclosed in a circle, occasionally with initials A.E.B. (Arthur E. Baggs) and/or H.T. (Hanna Tutt)

Contributions: Hand-thrown vases, bowls, and tiles with conventionalized design under a matte glaze.

“The Marblehead Pottery stands for simplicity — all that is bizarre and freakish have been avoided. It stands for quiet, subdued colors, for severe conventionalism in design, and for careful and through workmanship in all details.” – House Beautiful, 1912.

In 1904, the picturesque fishing village of Marblehead, Massachusetts, provided the overwrought patients of Dr. Herbert J. Hall with a relaxing environment in which they could recuperate. To aid them in their recovery, Dr. Hall established the handcraft shops, where each patient could “…under supervision, partake of certain occupational therapy in the form of arts and crafts.” As Dr. Hall explained in 1908, his intent was to provide his nervously worn out patients the blessing and privilege of quiet manual work, whereas apprentices they could learn again gradually and without haste to use their hand and brain in a normal wholesome way.” Among the crafts with which they could experiment in the former clubhouse that served as the Handcraft shops were metalwork, woodcarving, weaving, tiles, and pottery, the last inspired by the nearby Beverly Pottery (1866-1904).

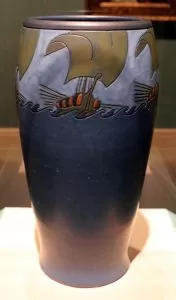

Marblehead Pottery in the Indianapolis Museum of Art, November 1, 2016. Photo attributed to Wikimedia Commons user Sailko

To help organize and manage the pottery works, Dr. Hall contacted nineteen-year-old Arthur E. Baggs, who had been recommended by his former ceramics instructor Charles S. Binns (1857-1934). For the first three years, Baggs and his patient-potters experimented with various forms and struggled to establish a studio and pottery operation with a consistent style and steady output. By 1908, production of simple, well-designed shapes and severely conventional decoration, clearly reflective of both the philosophy of Charles Binns and the current Arts and Crafts movement, had reached nearly 200 pieces per week. Realizing that the potteries potential could only be hampered by tying it too closely to the sanitarium and its temporary patient help, Baggs began the weaning process by hiring a small staff of full-time designers, artists, and potters. Among them were Hannah Tutt, decorator; Maude Milner and Arthur Hennessey, designers; and Englishmen John Swallow, potter; most remained with the pottery for several years. By 1915, it was apparent that Marblehead Pottery had outgrown its original intent, and it was agreed that Arthur Baggs would become its sole owner.

The simple forms and soft matte-glazed decorations appealed to an Arts and Crafts-conscious public. While popular designs were often repeated, vases and bowls continued to be hand-thrown and individually decorated by the artist, ensuring their clients that no two items — with the exception of tiles and molded bookends — could ever be identical. Early designs occasionally featured incised Indian motifs over a red clay body, and early wares can often be distinguished by their wide foot rims and rough bottoms compared with the narrow smooth bottoms of the later vases. Early pieces had often designs of nautical influence, such as stylized waves or harpoons.

Earthenware Marblehead Pottery vase (ca 1915–1920) A gift from Robert A. Ellison Jr. to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (2017) Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Other motifs found on Marblehead Pottery include insects, flowers, birds, seashells, animals, fish, and sailing ships; but as Martin Eidelberg observed in 1972, “More important than the motif, however, is its treatment: the design is conventionalized into flat, abstract patterns. There is often an insistence on a rigid, vertical stem, and many of the patterns are purely geometrical.” 15 years later, Eidelberg went on to state that “typical of the new sparse mode, Walrath and Marblehead shrank the design elements into linear, vertical or horizontal patterns and vastly increased the negative spaces of the ground. There was only one step left to take, and Baggs took it. He pushed past conventionalization into non-representational design through the use of geometric motifs.”

Essential to the Arts and Crafts style was the matte glaze popularized by Grueby, Hampshire, and Teco potteries prior to Marblehead’s entrance. In contrast to Rookwood’s version, the popular vellum matte glaze, the matte glaze that Baggs and his associates developed, “is at once the color, the design, and the surface — fused by the kiln into an immutable whole, a three-dimensional object of uniform surface patterned with color and devoid of all depth, gloss, or visual trickery.”

If you want to add some examples of high quality Marblehead Pottery, you’ll have the opportunity to bid on two pieces of amazing quality Marblehead Pottery at the October 12th Craftsman Gala – now offering absentee bids as well as over-the-phone proxies during the live auction. For more information, please go to the following website to learn more about the Craftsman Gala auctions and how you can participate either in person or from home.

https://www.stickleymuseum.org/support/the-craftsman-gala/2019-auction-guide.html