The Eccentric Ohr: A Profile in “Unbridled Creativity”

The following text is an excerpt regarding George Ohr Pottery from “The Official Price Guide to American Arts and Crafts: Third Edition”

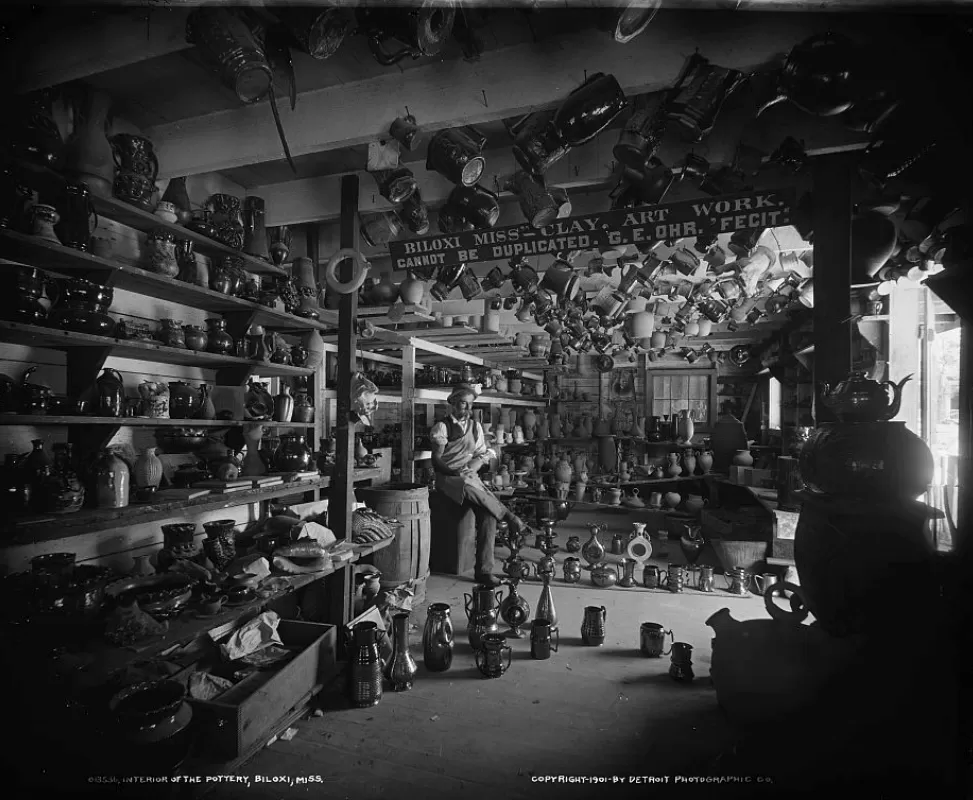

Interior of the George E. Ohr pottery workshop, Biloxi, Mississippi. Detroit Publishing Co. [Public domain]

“I send you four pieces, but it is as easy to pass judgment on my productions from four pieces as it would be to take four lines from Shakespeare and guess the rest.”

– George Ohr, 1905

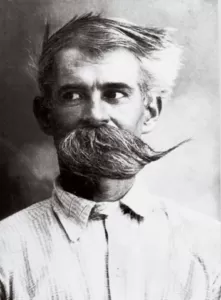

Photo of George Ohr. Photo courtesy of Robert Brooks/Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art [Public domain]

Ounce for ounce, the best work of George Ohr is now worth more than its weight in gold, but several years before his death in 1918, George Ohr, frustrated at the public’s failure to respond favorably to his life’s work, packed his inventory of pottery in boxes and retired. Most of it remained untouched until 1972, when an astute collector managed to buy nearly the entire inventory from the potter’s family. Since that time, both the works and the reputation of the infamous “Mad Potter of Biloxi” have spread across the country.

While many of Ohr’s contemporaries did not like him or his pottery, none could ignore him. Ohr managed to offend and confuse the austere Arts and Crafts reformers as carelessly as their staunch Victorian predecessors. Early historian E. A. Barber described his work as “twisted, crushed, folded, dented, and crinkled in grotesque and occasionally artistic shapes.” For many, Ohr’s eccentric behavior and his bizarre forms overshadowed the technical aspect of his pottery. Using local clay, he dug by hand from a nearby riverbank and hauled to his pottery in a wheelbarrow, Ohr was able to create eggshell-thin vessels of extraordinary quality, but dissatisfied with their state silhouettes, he proceeded to “dig his fingers into the moist, plastic clay of his perfectly executed, wheel-thrown vessels…twisting, crinkling, indenting, folding, ruffling, lobing, off-centering, and conjoining” until he had created forms never before imagined, let alone seen by most people.

Bisque pottery by George Ohr, ca. 1903-1907, on display at the Berkeley Art Museum Pacific Film Archive. Photo by Jim Heaphy. Cullen328 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Ohr’s creations, however, while reflections of a rebellious nature, were the work of a genius rather than a huckster promoting a gimmick. Scholars in search of a source for his inspiration have attributed it to nearly everything from Pennsylvania fold art to Victorian glassware to the pottery of the American Indians; a study in frustration, it is a reflection not so much of their efforts as of Ohr’s unbridled creativity. Less concerned than scholars with the inspiration for his work, Ohr was relentless in his task. “No two pieces alike,” he declared at exhibitions where he turned, twisted, and fired vases in a portable kiln before an audiences of curious bystanders. Their failure to support his unusual pottery prompted him to declare toward the end of his career, “If it were not for the housewives of Biloxi who have a constant need of flowerpots, water coolers, and flues, the family Ohr would often go hungry.”

Intrigued by George Ohr? Read more about George Ohr Pottery and its eccentric founder by picking up a copy of the Official Price Guide to American Arts and Crafts by David Rago and Bruce Johnson and in February of 2020, come see Ellen Lippert’s presentation of “George Ohr: Sophisticate or Rube” during the 33rd National Arts and Crafts Conference.