To Refinish — or Not To Refinish?

Collecting and living with Arts and Crafts furniture carries with it both responsibilities and challenges. We have a responsibility to care for, protect it, and preserve its original design, construction, and finish. But what do we do when the piece no longer looks like it did originally?

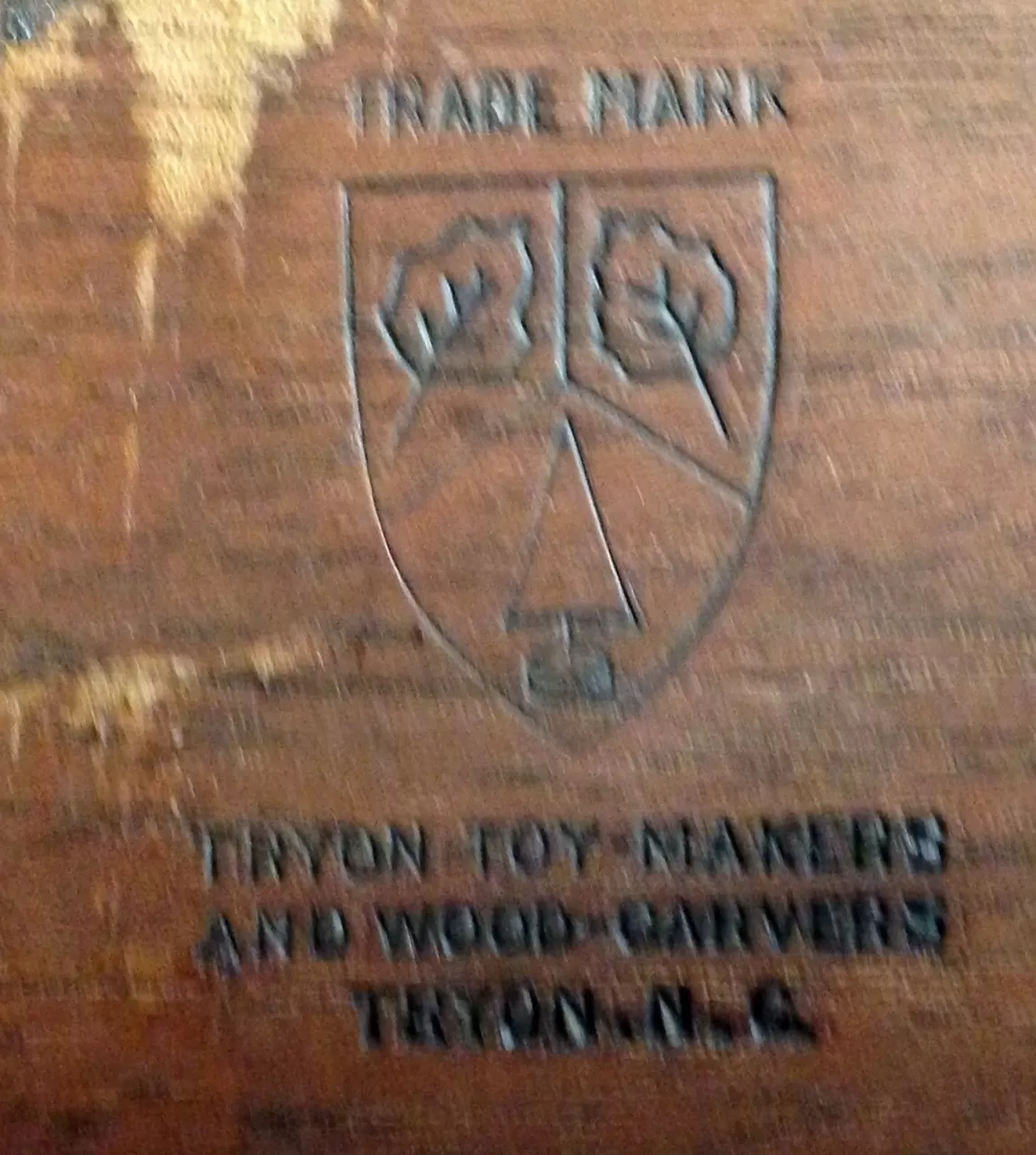

This challenge arose recently when a friend sent me photographs of a c. 1920-1930 walnut table made by the Tryon (NC) Toymakers and Woodcarvers, an Arts and Crafts enterprise formed by Eleanor Vance and Charlotte Yale after leaving Biltmore Estate Industries, which they formed and managed in Asheville from 1904-1915.

While the legs and apron appear to have their original color and finish, the top had been badly abused. Multiple white and black rings and stains most likely were caused by standing water on a weak finish. As soon as I saw the pictures, I was reminded of a magazine article I had found in Eleanor Vance’s papers in which a reporter wrote that their furniture was finished with varnish. In the margin either Vance or Yale had scrawled, “We never used varnish.”

Perhaps they should have.

That era’s alternative to an oil-based varnish would have been either paste wax or shellac, neither of which have strong resistance to water, heat, or hard daily use. Regardless of the finish, the table illustrates a familiar dilemma and debate: when is refinishing justified?

Naturally, I weighed in with my opinion.

Obviously, if an original finish can be retained with a careful cleaning and a coat of paste wax, that is the best route. Collectors and curators agree that an original finish, even if not perfect, enhances the value of an antique.

If the original finish had previously been removed and replaced by an earlier refinisher, then a second and more proper refinishing would be justified. In that case I would use a solvent, not sandpaper, to dissolve the finish. I would not attempt to sand off every scratch and stain, as the goal would be to replace the finish, not make the wood look brand new.

But what if this is the original finish, badly stained and battered?

Then the debate begins.

A purist would insist on nothing more than a coat of paste wax over the existing finish and damage.

At the other end of the spectrum would be the call for a complete refinishing, removing the finish, stains, and damage, justifying that course of action as returning the top to how the original artisan would have wanted it to look.

In this particular situation, I would strike a compromise. I would begin by carefully cleaning the original finish on the legs and apron with a soft cloth lightly dampened with mineral spirits, checking to make sure my cloth was only removing old dirt, polish and wax, and not the finish. I would then protect the legs and apron with a coat of quality paste wax.

I would next use a solvent, such as denatured alcohol and/or lacquer thinner, and a cloth to remove the finish on the top. This typically erases the majority of white marks, which are caused by moisture trapped in the weak finish. I would not bleach out or sand off the black marks and scratches. To do so would dramatically alter the appearance of the top.

Instead, I would only apply a wood stain if it was needed to match the original color of the legs. I would finish the top with a satin sheen of lacquer or shellac, rubbed out afterwards with a coat of paste wax and a soft cloth.

While neither of these two finishes are as durable as modern polyurethane finishes, they are historically accurate to the era during which this table was made. So long as the table is used with the care deserved by any antique, i.e. with coasters, placemats, table runners, and no direct sunlight, either satin lacquer or shellac topped with paste wax will protect the wood while not looking brand new.

Finally, every situation is unique, so be sure to carefully evaluate the condition, and consider all the options, always mindful of the adage: First, do no harm.

Good Luck!

Bruce Johnson