Arts and Crafts Bones

I have always been fascinated with trying to find the original sites of any Arts and Crafts firms I was researching. It began even as a teenager, when I drove out into the Illinois countryside near where I was born, parked my blue 1961 Chevy Bel Air (should never have let that get away) at the edge of a woods, and hacked my way through the dense brush to discover the brick ruins of the kilns and smokestacks of the 1890s Griffin Tile Works.

So, it came as no surprise when last week Jim Messineo of JMW Antiques captured my attention during his virtual Small Group Discussion with his story of accidentally finding the site of the Grueby Pottery in Boston. Not only did Jim find in the dirt discarded shards of matte green pottery, but he actually found one with an intact Grueby shopmark impressed in the hard clay.

Above pictures courtesy of Jim Messineo

Something like that would forever sit atop my desk!

I’ve been fortunate on my travels to have toured several restored Arts and Crafts sites and structures, from Craftsman Farms and the Roycroft Campus to the Gamble House and both of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin homes and studios.

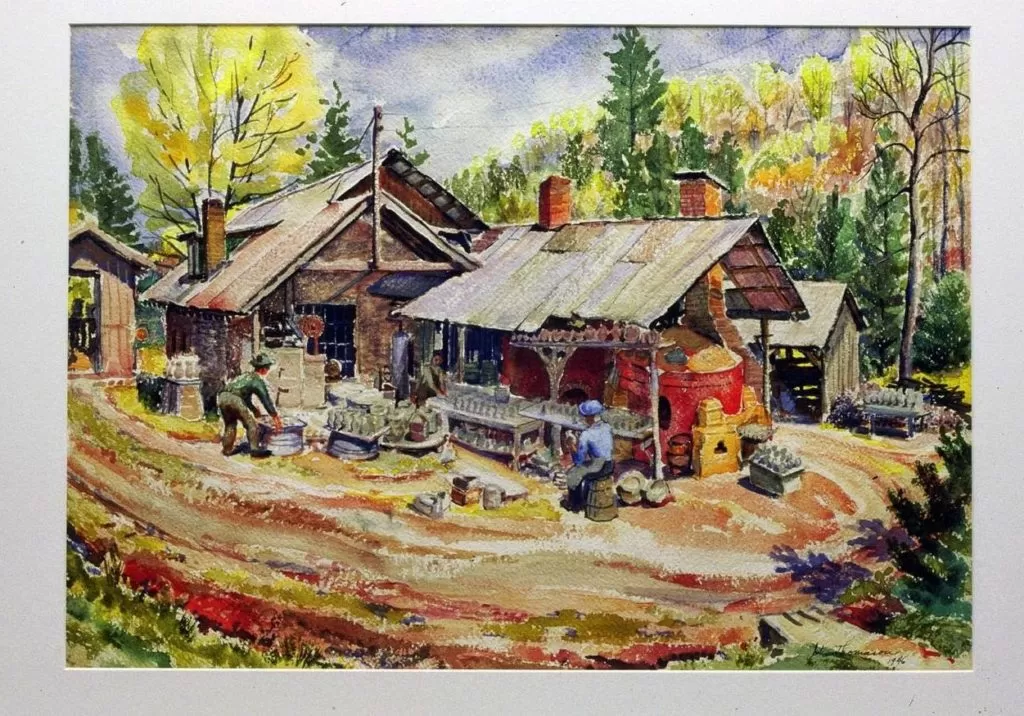

But I remember just as clearly David Rudd taking me to the site of Gustav Stickley’s original Arts and Crafts factory in Syracuse, where just one brick wall still stands. Closer to home, when I was researching silversmith William Waldo Dodge I walked around the sites of both of his former workshops. I did the same when preparing to write about Pisgah Forest Pottery and Biltmore Estate Industries, two additional Asheville Arts and Crafts firms with some surviving remnants of their original buildings.

Pisgah Pottery caption: Pisgah Forest Pottery, 1946 Photo courtesy of Rodney Leftwich.

But there’s always the one that got away.

As he designed and built the 1913 Grove Park Inn, Frederick Loring Seely also constructed a few cottages on the grounds. Most were intended for guests who insisted on bringing their children, for Seely, although a father of five, disliked having children disturbing his guests, many of whom were businessmen from New York, Chicago, and Washington.

But one of these first buildings, named Azalea Hall, became known simply as the Carpenters’ Shop. It remained in service even after the July 12, 1913, grand opening, for the sixth-floor rooms had not yet been finished and Seely was always embarking on changes and additions he deemed necessary to the resort hotel.

In 1917, suspecting the day would come when he and owner E.W. Grove would no longer be able to work together, Fred Seely bought Biltmore Estate Industries from the widow Edith Vanderbilt. He gradually moved the woodworkers, woodcarvers, and weavers of homespun cloth into six quaint, English-style buildings he built next to the famed hotel. They remain there today, fully restored to their Arts and Crafts glory.

Tucked away between the Grove Park Inn and Biltmore Industries was the Carpenters’ Shop, which in 1917 Seely turned into one of the woodworkers’ shops. It remained there, practically unnoticed, for decades. I first toured the Grove Park Inn in 1985, soon after moving to North Carolina, and paid it no attention then or in any of my planning sessions prior to our first Arts and Crafts Conference in 1988, for at that time I had never heard of Biltmore Industries.

The following year, however, I began researching Biltmore Industries and the buildings Fred Seely had constructed for his workers. When it dawned on me that the cottage next to the Grove Park Inn had housed the woodworking equipment, I immediately asked about it.

“Oh, that,” came the reply. “We tore it down in 1988 for parking.”

Until next week,

“Nothing is more expensive than a missed opportunity.” — H. Jackson Brown JR.

Bruce