Changing Times

What a difference a few decades can make.

Soon after the Grove Park Inn opened on July 12, 1913, general manager Frederick L. Seely printed a string-bound, informational brochure intended to entice people across the country to come to what he touted as “the finest resort hotel in the world.”

On the cover he proclaimed that the hotel is “absolutely fireproof,” a reflection of the fact that hotel fires were commonplace at a time when old wooden hotels were being retro-fitted with often questionable electrical wiring by less than qualified individuals.

He goes on to declare, “We do not entertain conventions. We have found that they disturb the homelike atmosphere of the Inn and interfere with the comfort of guests.”

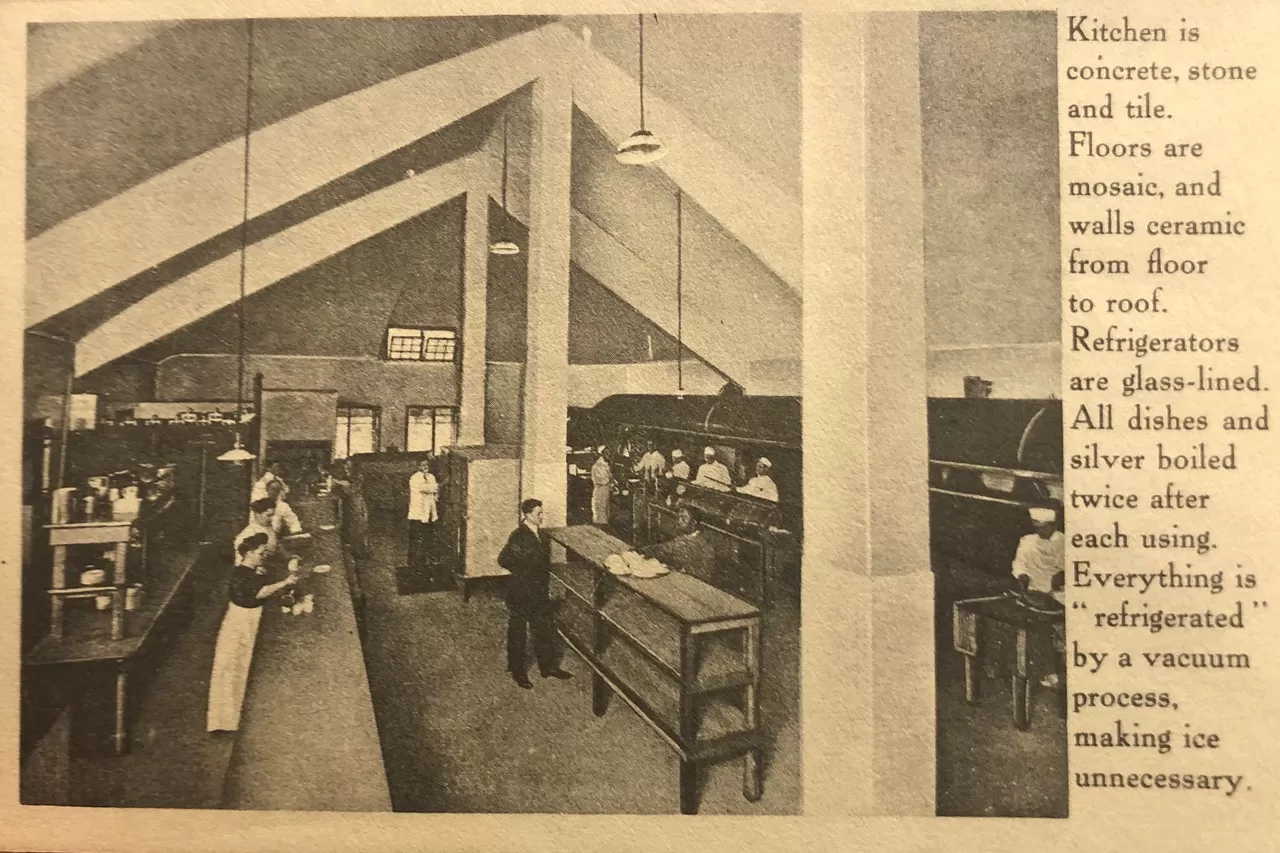

Sanitation was a critical concern during the Arts and Crafts era, as people began to recognize the role germs played in the spread of illnesses and disease. Fred Seely hoped to allay any fears by pointing out that in the kitchen he designed “the walls are of white glazed tile and the floors white ceramic tile. All dishes are boiled after each using and even the silver and drinking glasses are boiled. All refrigeration is artificial; ice is not used.”

Further on he reports, “The climate of Asheville is wholesome and invigorating. The altitude forbids humidity and heat even on the warmest summer days.” And for those in fear of contracting malaria or yellow fever, Seely mandated, “There are no mosquitoes.”

Fast-forward one hundred years and any recent description of the Grove Park Inn will invariably highlight the resort’s Arts and Crafts heritage, the critical roles of founder Edwin Wiley Grove and designer Frederick Loring Seely, the collection of Arts and Crafts antiques, and the long list of famous individuals who have stayed there.

Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone Jr., editor Horatio Seymour, Henry Ford, and Fred Seely.

But what would have been the tone of a brochure written in the 1950s, at a time when the hotel was not yet historic and when, in the words of my father, having ‘mission oak’ furniture meant that you were poor?

A good friend of mine recently answered that question with the gift of a promotional brochure published by the Grove Park Inn around 1950. While the 150 guest rooms still contained their Arts and Crafts furniture, it was obvious that it had all been stripped, sanded, and robbed of its original dark finish, the rooms then having been “decorated in the modern manner.” There was no mention of the Arts and Crafts style nor of the Roycrofters and their hand-hammered lighting fixtures, even though several were still in use. Worse yet, the writer omitted even a passing reference to either E.W. Grove or Fred L. Seely.

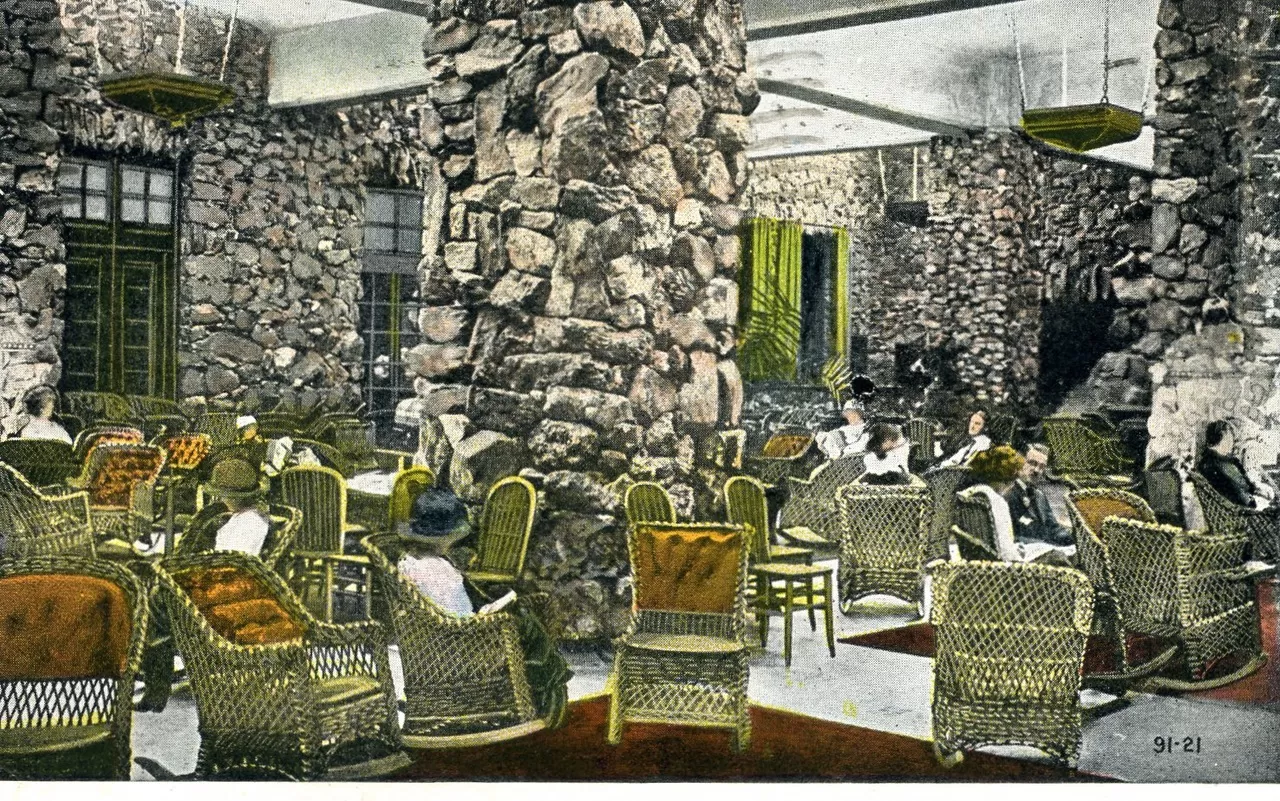

In describing the Great Hall, the writer notes that “it reflects peaceful charm and quiet, and is the center for recreation, conversation, games, and social gathering.” In addition, “a smart gathering place is the new cocktail lounge. Strikingly original, a perfect spot for leisure hours.”

I found it interesting to note that while Grove and Seely discouraged bringing children to the Inn, feeling they interfered “with the comfort of guests,” by the 1950s that attitude had changed: “A well-equipped playground, with all the things that delight the hearts of children, is provided. They will have a grand time and you will be happy in the knowledge that they are safe and busily enjoying themselves.”

The differences between brochures written in 1913, 1950, and 2020 are insightful as they reflect changing societal attitudes and expectations, but what has not changed over the course of more than a century is the fact that “the Grove Park Inn is a unique structure, built on an entirely different plan from the average resort hotel. The idea was to build a big home where every modern convenience could be had, but with all the old-fashioned qualities of genuineness with no sham.”

Until next week,

“Things made by Nature, assisted by artists, carry sentiment.” – Frederick L. Seely

Bruce