“J. E. B”

For years, I only knew her as the initials “J.E.B.”

Hand-written in tiny script, always neatly, I would find them tucked away at the end of notes she had written me, starting as early as 1914, having no idea who I might be.

“This is our first ad in House Beautiful,” she wrote in her scrapbook, carefully dating it September of 1914.

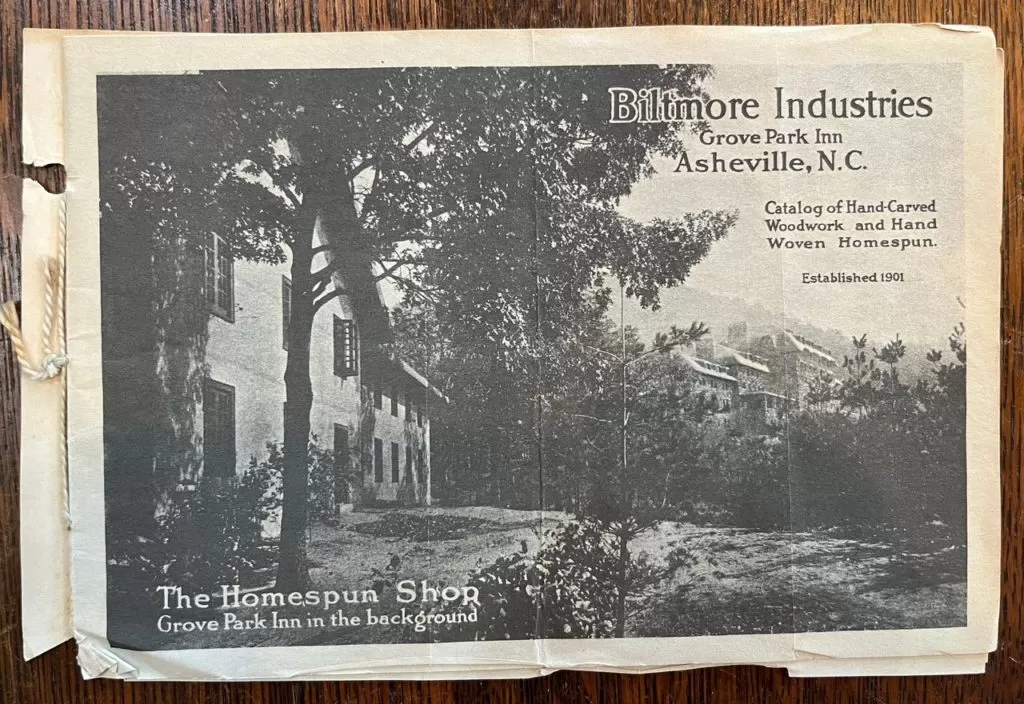

On the inside back cover of the first Biltmore Industries Arts and Crafts catalog, she made sure I knew what it was: “First catalogues after Mr. Seely bought Industries. Started using them December 29, 1917. 25,000 ordered and received.” Like the ads she had precisely clipped, she thought to save one of those first catalogs, adding it to her carefully preserved scrapbook for someone to find in the office where she had worked for 36 years.

More notes followed. If she liked a particular color of Biltmore homespun, hand-woven on their massive oak looms, she would glue a tuft of wool or small piece of fabric onto a scrapbook page, citing the name beneath it: Carolina Blue, Forest Green, Coolidge Red, and J.E.B.’s personal favorite – Autumn Bronze.

Her boss, Frederick Loring Seely, had designed, furnished, and managed the Grove Park Inn from 1914 through 1927. Seely loved to dictate letters, sometimes as many as a dozen in a single day. And she kept carbon copies of each one – sorted, labeled, and filed away. Soon, at the close of each one, I spotted them again – JEB:FS. Her initials first began appearing next to his in 1917 and were still there in 1942, when Fred Seely passed away.

J.E.B. had to have been good — and she must have been tough.

Between just 1917 and 1920 Fred Seely hired – and drove away – four general managers at Biltmore Industries. He was demanding, once insisting that his manager fire one of his best woodworkers for being 15 minutes late to the workshop. When the manager refused, he was soon gone, too. Another time Seely berated a night manager because he thought the pay phone in the hotel lobby smelled badly.

But J.E.B. hung in there, typing his letters and listening to his rants.

And she soon became general manager number five.

In 1922, when she was 31 years old and single, Fred Seely sent her by herself on an ocean liner headed to Scotland for two months to learn all she could about hand-weaving homespun cloth. Judging by her journal, it turns out the weather, the food, the accommodations, her acceptance, and J.E.B. were all miserable.

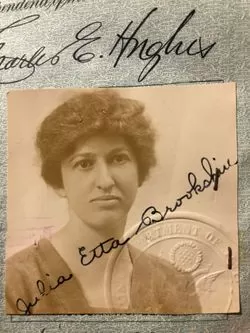

But last week I finally found Her — Julia Etta Brookshire.

She had married Bill Lynch in 1924, soon after her return from Scotland, which made tracking her down that much more difficult. It seems they had a good life: he was a successful farmer just a few miles from where I now live, and she continued to serve as Seely’s general manager after moving here in the country. Bill, however, died in 1954, at the age of 72.

Life was tough for Julia after that, as both her parents were dead, she and Bill had no close siblings, and they had no children of their own. When Bill died, she had his headstone and hers placed beside each other in the small Gashes Creek Cemetery outside Asheville. After that, Julia struggled, passing away 14 years later in 1968 in a small room inside a local nursing home, death coming, in one of those horrid newspaper clichés, “after a long illness.”

It was a painfully brief obituary.

She was buried beside Bill and her parents, but no one had come forward in 1968 to pay for the missing date on her soiled headstone. I spent an hour with Julia last Friday, scrubbing her stone before making arrangements to have the two missing numbers carved in her tombstone.

And promising her that when my book was complete, others would know who Julia Etta Brookshire was – and all she had accomplished as an Arts and Crafts woodcarver, a weaver of homespun cloth, and the office manager for three decades of what had been the largest hand-weaving enterprise in the entire country.

Until next time,

“Carve your name on hearts, not tombstones. A legacy is etched into the minds of others and the stories they share about you.” ― Shannon Alder

Bruce