“Lest We Forget:” My Search for Elbert at Kinsale’s Old Head Tower

by Kate Nixon

12 Miles.

A sunny day at Kinsale’s Old Head looking at the Atlantic Ocean, part of the “Wild Atlantic Way.”

As I looked out towards the horizon on Old Head point in Kinsale, I attempted to place where the 12-mile point might be: that spot where the locals looked out in horror to the sight of the RMS Lusitania sinking. Old Head was the closest point of land to where that ship sank, where Elbert and Alice Hubbard were two of 1,198 lives lost on the Liverpool-Queenstown-New York route. On a rare sunny Saturday in Ireland, my father and I ventured out to the Old Head of Kinsale to visit the Lusitania Museum and Memorial Gardens after finding out about a special sculpture with the names of the crew and passengers inscribed. Off I went, determined to find their names etched and potentially some reference to the Hubbards, a name most likely foreign to the Irish but one I’ve heard countlessly for the last five years as an American in the Arts and Crafts community.

A model of the RMS Lusitania in the second floor of the museum.

The museum itself is located on the second floor in a small signal tower, originally number 25 of 81 towers built by the English along the Irish coastline from Dublin to Donegal all within sight of each other. While it spent most of its existence in ruins, Old Head was the first of Ireland’s Napoleonic signal towers to be restored, marking the 100-year centenary of the sinking of the Lusitania. It was this tower on that fateful day, May 7th, 1915 that locals saw the sinking ship and rushed their boats 12 miles out to save who they could. It took 18 minutes for the Lusitania to completely submerge and after the efforts of the seaside locals and the tower crew rushing a number of boats out to sea, only a small number of the passengers were saved.

An image of the RMS Lusitania survivors in the Old Head tower museum in Kinsale.

The events are played out through artifacts, framed articles, and other documents kept on the second floor of the tower, a small space to navigate, but memorable as I saw a framed image of a remnant of a ladies’ shoe found in a fishing net. The chances are incredibly minute that the shoe was Alice’s, made even more minute from the presence of the embossed name of a Northern English shoe company. Additionally found on that floor was a money belt in tact, donated by the relative of a Lusitania survivor, another Alice — Alice Middleton McDougal, who had written a poem about her experience. Located directly across the way was a newspaper spread, containing portraits of two children and a woman – newly married — who were among the drowned. It is a sobering experience seeing images of young children who met such an unfortunate and intense ending.

Among the several images, documents and plaques was an image of survivors saved by Kinsale locals: ten men with newsboys caps and jackets standing tall with only a few forcing smiles for the camera and others looking down, perhaps attempting to process the trauma, grieving a travel partner, or feeling the first pangs of survivor’s guilt. Perhaps one of these survivors knew Elbert and had engaged him in a brief conversation. It made me wonder: what would have happened if just a few elements changed? If Elbert, Alice and Fred were on the other side of the boat engaged in conversation with one of these men, would the Hubbards have been among the survivors and been able to live out the rest of their lives? My thoughts were interrupted as my eyes rested on a plaque with the centenary logo and a headline title “Lest We Forget” in appreciation of the locals of the Old Head at Kinsale who rushed out to sea to bring home those still fighting for their lives. My search for the name “Hubbard” softened and I silently agreed that the bravery of the good and kind folk of Kinsale that day saved the precious lives of those few men. While I wish the Hubbards were among them, the actions of the Irish deserve recognition and reverence.

A view from the top of the Old Head Tower in Kinsale, overlooking the Lusitania Memorial Garden and the Atlantic Ocean.

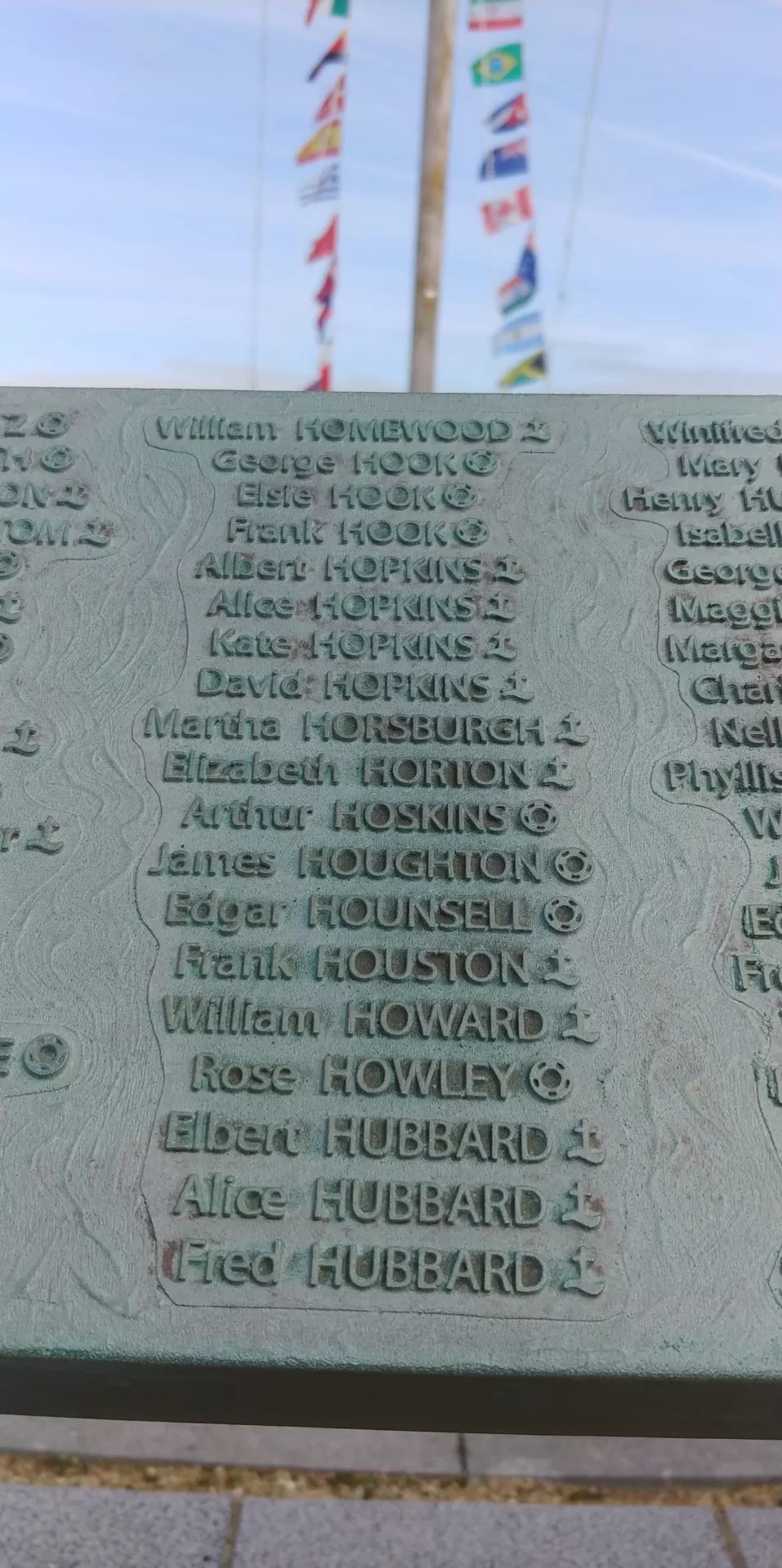

After viewing the museum, I made my way to the Memorial Garden, a small but meaningful large circle of space with benches, with the mast of the Lusitania in the middle with all flags of the nationalities of those on its final voyage. A 20-meter (66 feet) bronze sculpture in the form of a wave, on the outskirts of the inner circle, lists the names of all crew and passengers aboard the Lusitania, accompanied by symbols next to their names indicating their fate. At long last, I had found Hubbard’s name where I had expected to.

The names of Elbert and Alice Hubbard inscribed on the 20-meter bronze sculpture in the Memorial Garden at Old Head, Kinsale.

There they were: each of their names listed with small metal crosses next to each name. I looked beyond the bronze plate, through the mast strewn with national flags, and towards the sea. On a day like this, this calm and quiet day at sea seemed like a lovely final resting place for the Hubbards, And yet. Naturally as a steward of the Arts and Crafts movement, it broke my heart a little that no one here knew who the Hubbards were.

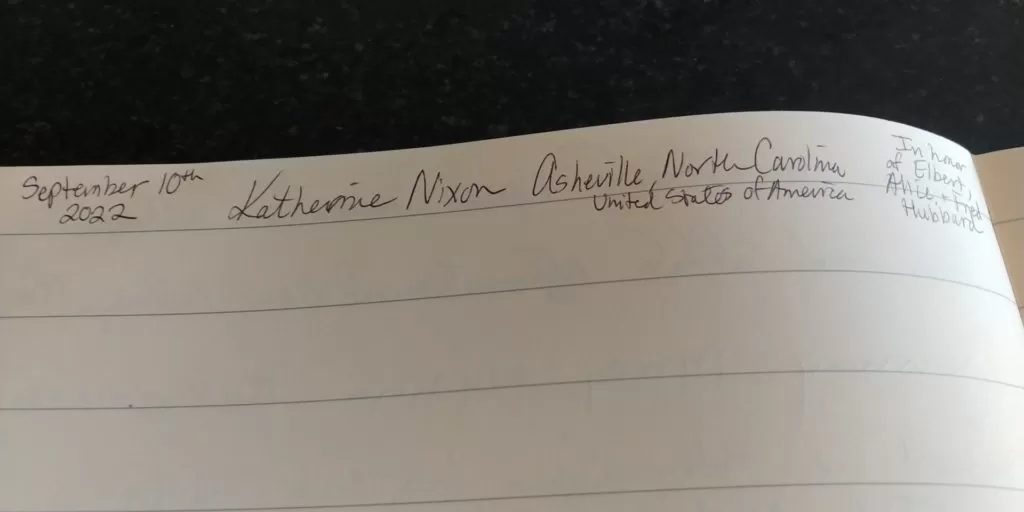

And so I ventured to the small bookstore and admission office and decided to sponsor a slate, offering a small amount of Euros to support this project with the Hubbard name on it. Each sponsor would get a certificate and a place to inscribe a message in the official museum book. With a smile, I wrote in the book the date, my name, the town of Asheville, N.C. and the message: “In Honor of Elbert and Alice Hubbard.”

Until next time,

“It’s not so much lest we forget, as lest we remember. Because you should realise the Cenotaph and the Last Post and all that stuff is concerned, there’s no better way of forgetting something than by commemorating it.”

Next week….

A Surprise Trip

– Kate

My inscription and sponsoring the Hubbard slate.