Lucky Penny

It all started at my grandmother’s kitchen table, a late 19th-century walnut dropleaf table she and my grandfather had bought second-hand from Maurice Peterson during the Great Depression, just after they first started farming on eighty acres of rented Illinois prairie. It was worn, but well-polished, with annual coats of glossy shellac applied with a hog-bristle brush my grandmother carefully cleaned with denatured alcohol after each spring’s application.

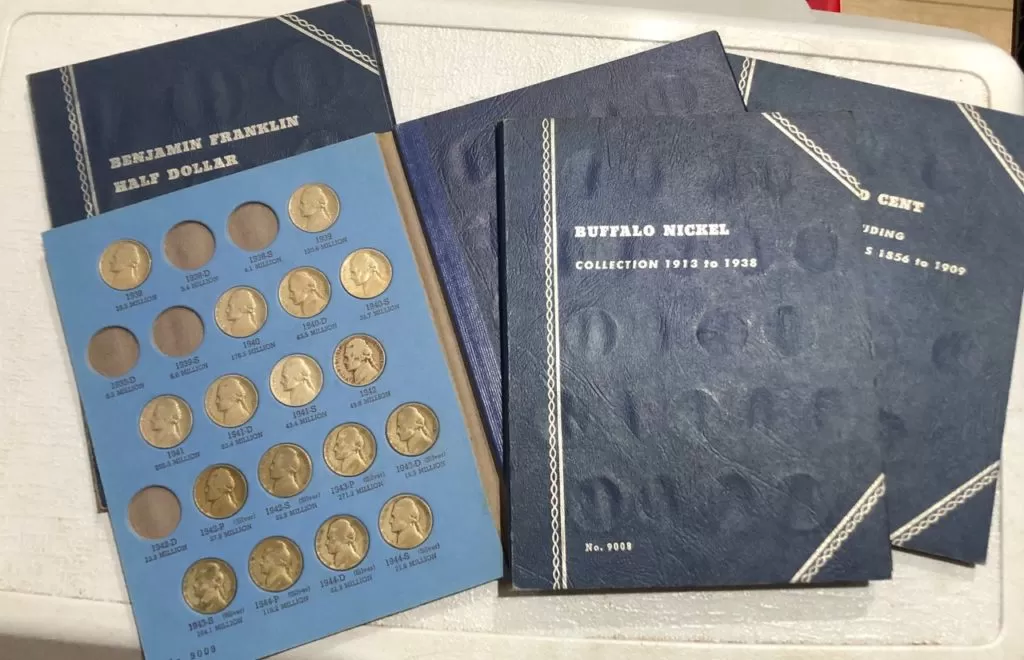

On this day the table had been carefully rolled on its four oiled porcelain castors across the varnished heart pine kitchen floor until there was room enough to raise both oval dropleaves until the hidden iron supports snapped reassuringly into place, providing a ten-year-old boy with ample room to plant both his elbows. From a Woolworth’s department store bag my grandmother pulled out my birthday present: five blue folding Whitman coin books, one each for Lincoln pennies, Jefferson nickels, Roosevelt dimes, Washington quarters, and Franklin half dollars. The rows of empty slots beckoned me like a lighthouse to a wandering sailor. Beneath each slot was printed the year and location where each coin had been minted: 1914-D for Denver; 1914-S for San Francisco; and no letter beneath the date indicated the source had been the Philadelphia mint.

As I sat in my grandmother’s kitchen with my empty Whitman folder opened before me, to my amazement, my grandmother poured a Folger’s coffee can of Lincoln pennies out across her walnut table. In my young life I had never seen so many gleaming copper pennies. As my mother began turning them over, face up, I picked up the first penny, read the date and mint mark, found its empty slot, and pressed it into its new home with my thumb. My grandmother beamed with pride, explaining to me that since a child she had always saved any pennies she had found for good luck.

Unless it was in better condition, any duplicate went back into her Folger’s can and returned to a shelf in the basement behind the carefully labeled jars of stewed tomatoes we had picked from my mother’s garden. We sorted through three cans of Lincoln pennies that day, and all three cans of lucky pennies were most likely still on the shelf in her basement when my grandmother gently passed away in her sleep at the age of 92.

Finished, I looked up at her. She pointed to my Whitman folder, where all but one of the critical 1909 slots had been filled.

“I had all of them,” she explained. “My mother died in 1909, when I was four, and so later I decided to save every 1909 penny I could find, in her memory, which is what started me saving pennies. And I know more than one of them had an “S” on it. I thought I had put them all in one of these cans.”

Of course, the one coin which was missing was the rarest of them all: the 1909-S with the initials “V.D.B.” honoring the designer Victor D. Brenner.

That day she and my mother went through all of her cupboards, desks, and drawers looking for it, while I continued to marvel over the number of slots I had already filled, but the rare San Francisco penny which Victor D. Brenner had designed was never found.

And that was the one I never could bring myself to buy. I still have my blue Whitman folder, open here beside me right now, with nearly every slot from 1909 through 1940 filled, with just one exception. Each time I had the opportunity, each time I started to reach for my checkbook tucked in my back pocket, I figured this time I would buy it, just to finally complete that inaugural year of 1909.

But, so far, it has never seemed quite right.

Until next week,

“Often, the story of an artifact’s journey is more remarkable than the object itself.” ― Mackenzie Finklea, author

Bruce