Of Pigments and Printer’s Ink

My latest little journey took me to Santa Fe, where I met my oldest son Eric, who is finishing his doctorate in chemistry at the University of Utah. Fortunately, it didn’t take much to convince Eric to let his lasers cool in the lab over a long weekend while we explored Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

I knew that at the top of our list would be a visit to the Georgia O’Keefe Museum in Santa Fe, where they have assembled the most extensive collection of the prolific painter’s artwork. After living for several years in New York City with her husband, the famed photographer Alfred Stieglitz, in 1949 O’Keefe moved to New Mexico where she painted until her death in 1986 at the age of 99.

What I did not know until halfway through the museum’s documentary on her life was that O’Keefe was heavily influenced by Arthur Wesley Dow, the teacher and Arts and Crafts printmaker who also influenced nearly every 20th and 21st century Arts and Crafts printmaker.

The exhibit also included a print by Gustave Baumann (1881-1971), one of the most sought after Arts and Crafts printmakers who also lived and worked in the Southwest. Beneath the museum’s print I spotted a small, neatly typed notice stating that the studio of Gustave Baumann had been preserved and recreated across the street.

Needless to say, Eric and I soon headed across the street.

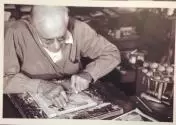

It took three museum employees to finally point the way to the small wooden door set into a low adobe building leading into the studio of Gustave Baumann. The one-room, permanent exhibit is so seldom visited that it was not even staffed, so Eric and I stood there, alone, standing next to his workbench, his easel, and his hand press, inhaling the scent of printer’s ink and dry pigments, carefully labeled in Baumann’s handwriting and stored in glass bottles.

For a moment I fully expected the artist to step back into the room and begin pulling prints from his press.

As a young man, after studying in the Midwest, Baumann’s wanderlust had taken him as far east as Cape Cod and as far west as Santa Fe, where he and his wife Jane lived for more than fifty years. Described as “possessing the hand of a craftsman and the heart of an artist,” Baumann would first sketch each scene on paper, then would return to his studio to transfer it to thirteen-inch squares of basswood. He then began the intricate process of carving away the negative spaces for each color planned for the print.

As one reviewer noted, “his prints are awash in brilliant, hand-ground pigments, simple and elegant studies rooted in a rural, wholesome America that manages to be both delicate and rugged, personal and mythic.”

Baumann’s prints immediately found an eager audience, as they were sold through galleries across the country, as well as to private collectors. He enjoyed a successful career, in part because his wife Jane served as his agent and business manager, shielding him from intruders, enabling the artist to work in his studio in solitude, pulling prints, experimenting with various colored pigments, and capturing on paper the haunting beauty of the Southwest landscape.

When once asked to describe his technique, Baumann remarked in his characteristic succinct tone, “Draw directly on the block whatever you want, then cut away whatever you don’t want, and print what is left.”

Until next Monday,

Let yourself be inspired.

Bruce

Note: To see examples of Gustave Baumann’s woodblock prints, just click here to go to our Facebook page.