A New Leather Seat

I love workshops.

I don’t care whether it’s a woodworking shop, a pottery studio, a stained-glass workplace, or a metalsmith’s workshop, I just love wandering around and looking at their machinery, their specialized tools, their custom workbenches, and all sorts of cool stuff that’s always hanging from the walls.

And I love inhaling the various aromas: freshly-milled oak, raw hide leather, heated flux beneath the red-hot tip of a soldering iron, lingering shellac fumes, or damp, earthy clay.

Last week I left my workshop and headed into Asheville in search of a two-foot square of hide leather for a Gustav Stickley ladder-back dining room chair. Had it not been for the stay-at-home orders hovering over us during this pandemic, this lonesome chair might still be hanging from the rafters in my barn.

I picked it up years ago in an Asheville antiques mall for a hundred dollars, knowing it needed a complete restoration: regluing, replacing missing color and an inappropriate modern finish, and recreating the original leather upholstered seat. But now that I had finished just about every project in my workshop, I rescued this poor chair from the rafters, wiped off the cobwebs, and restored the finish.

For the seat, I knew that I could order hide leather online, but leather suppliers use a unique system for measuring the thickness of leather. Instead of fractions, they use ounces, but it has nothing to do with how much the leather actually weighs. It is very confusing, and since a hide is never uniform in either thickness or in grain, and often has natural imperfections, it is worth the time to track down a source near you. These hides are much thicker than upholstery leather, which is thin and supple enough to be sewn. Leather for a chair seat has to be thick enough to support our weight without stretching or tearing, but thin enough that, when softened with water, it can be molded around the four seat rails.

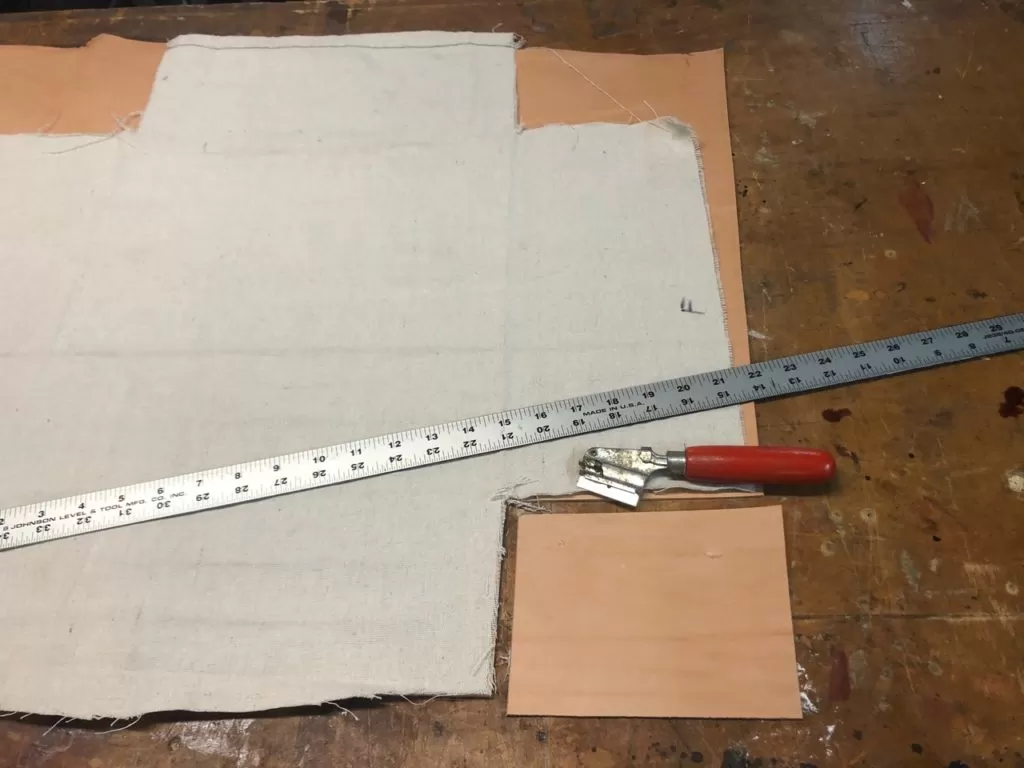

My source is an Asheville saddle shop, which has a downstairs workshop where they make and repair saddles, among other leather items. The leather workers seemed intrigued by my Stickley chair project, along with the canvas pattern I had cut to show them exactly how much leather I needed. Soon they were pulling out various hides, letting me feel the thickness and inspect each one for any distracting flaws. It did not take long for me to select a section of a hide, which was categorized as 5 ounces (5/64”) in thickness and cost $12 a square foot.

Using the lightweight canvas pattern I had precisely cut to fit the chair seat, I used a new razor blade and straightedge to slice through the hide leather. I then held it under the faucet of my utility sink, soaking each side with warm water until it became flexible.

While I waited for the leather to soften, I wrapped and tacked my canvas pattern to the seat, just as the workers had at Stickley’s factory. I then laid down the thin layer of original cotton batting I had saved and slipped my new leather over the top of the seat. (Note: as an option here and as a necessity on larger seats, you can weave upholstery webbing over the canvas before laying down the batting.)

While the leather was still damp and flexible, I stretched each of the four tails around the rails. You don’t have to apply a great deal of pressure to each tail, as the leather shrinks and tightens as it dries. I used my staple gun to hold the leather temporarily, then hammered in upholstery tacks to secure it to the rails. I have found that it is easier to then trim off the excess tail leather with a razor blade while the leather is still damp.

I will now give the leather seat a few days to completely dry before I add color, a finish, and tacks to it, which hopefully will make a column for a future edition.

Until next week,

“Generally, I’m mending things, which is interesting, because you learn a lot about why they broke.” – James Dyson, British inventor

Bruce