Rules of Disengagement

We’ve all known since high school that drinking and driving don’t mix, but now we need to add antiques to that formula.

A few weeks ago, an inebriated guest at the Omni Grove Park Inn swerved off course and collided with one of the Roycroft dining chairs on display near the Great Hall. Built in 1913, the solid oak chairs have survived nearly 110 years of use and abuse by countless guests, but have always endured intact.

This chair, however, landed hard on its right arm, breaking one of the vertical supports attached to the seat. The accident was caught on camera, as nearly everything in our lives is these days, so the hotel’s security staff arrived before the guilty guest could stumble off to his room. The next day the staff called me, sent me a picture of the broken arm, and asked what they should charge the guest for the damage and the needed repair.

A few days later, I picked up the GPI chair and brought it back to my workshop. Fortunately, the staff had been astute enough to gather the oak splinters off the floor and to save them in an envelope. This brings up “Rule #1 For All Repairs: Do not delay.” As soon as crisp edges get rounded, the pieces never fit snugly.

I could not tell if the two sizeable splinters they had collected accounted for all which were missing, so I first did a dry trial run. I clamped the pieces together without any glue to check the fit. To protect the oak from the metal jaws of my clamps, I could have used small pieces of softwood, but I also keep scraps of thick leather on hand to do the same. They are easier to cut than wood, and bend to fit contours.

Which brings us to “Rule #2 For All Repairs: First, do no harm.” Forcing the break further apart to insert the tip of my glue bottle might have caused even more damage to the antique chair. Instead, I filled a syringe with quality woodworkers’ glue and injected it deep into the joint.

Knowing from my dry run that the two splinters would fill the void in the chair, I then applied glue to all of the raw surfaces, slipped the loose pieces into place, and applied pressure with my clamps. The pressure forced the excess glue out onto the surface, which I immediately wiped off with a damp cloth. Letting the droplets of glue dry on the surface, however, with the intention to scrape or chisel them off later, is a mistake. Both the dried droplets of glue and your scraper or chisel can easily remove and damage the fragile finish.

Once the excess glue has been wiped off, however, does not mean you can leave. The combination of the liquid glue and pressure from the clamps can cause the splinters to slide out of place before the glue hardens. Check the splinters carefully for five to ten minutes, by which time the glue will have dried to the point where they won’t slide under your clamps.

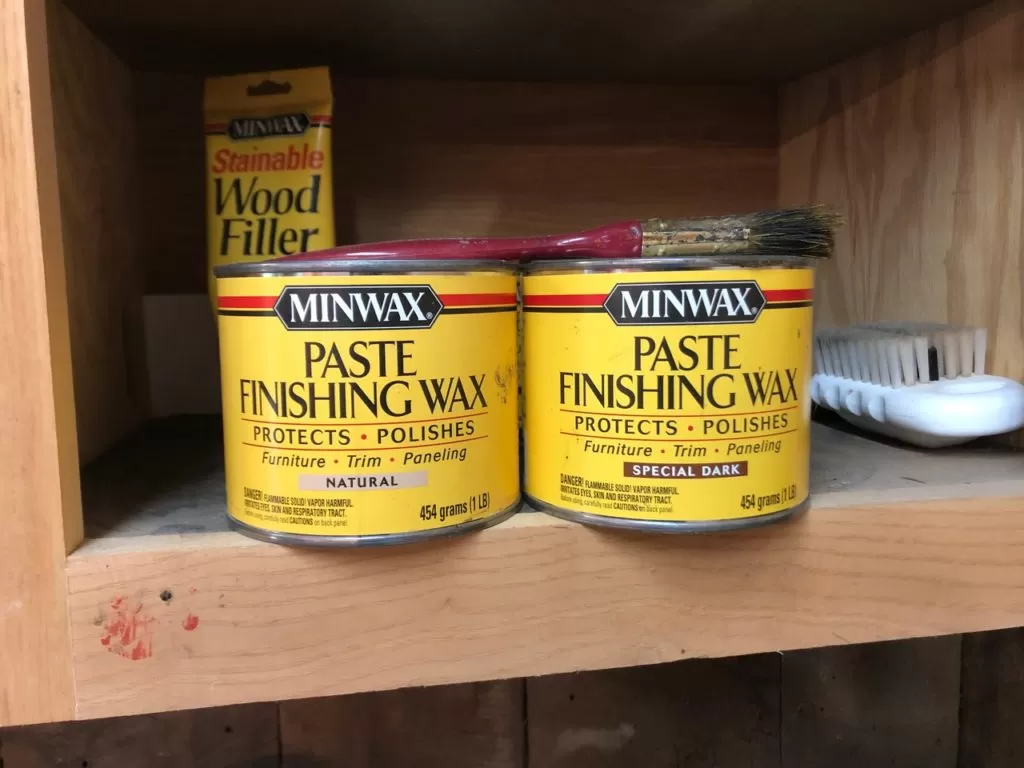

And since even the crisp edges around a break don’t always come together perfectly, I complete repairs like this with an application of dark paste wax to fill any small gaps in the wood.

Rest assured, once I finish touching up a few nicks and scratches, the oak Roycroft chair will return to the Grove Park Inn.

If he also returns, let’s hope the embarrassed guest has learned from his mistake.

Until next week,

“We all make mistakes, but what matters is how we go back and fix them.” ― Rwynn Christian

Bruce