Sentimental for Cemeteries

I have a thing for cemeteries. Not a ghoulish, midnight on Halloween obsession, but more like a combination of historical research mixed with a curiosity about the inhabitants of those small plots of landscape.

As a small child, Memorial Day observances always included a march with the Boy Scouts to our town’s two cemeteries, where a brief memorial service was followed by our World War II veterans firing a salute over their fallen friends. Once I became a teenager, I inherited the job of mowing an old country cemetery three miles outside of town. My dad would drive me out in his truck, start the mower from the storage shed, then leave me there, along with the lunch my mom had fixed, for the day. Over the course of three summers of mowing and trimming the grass around their tombstones, I felt I came to know the inhabitants of Hopewell Cemetery, at least to the extent my teenage imagination could envision what their often brief lives had been like – and why so many ended so early.

My father’s parents were also there. My grandfather was just 34 years old when on a cold, snowy night he was crushed to death between two railroad cars in a switching yard. My grandmother raised my father and his two younger brothers until she was struck down with ovarian cancer three years later. I learned from my father that their hard lives and their early deaths were not that uncommon in their era.

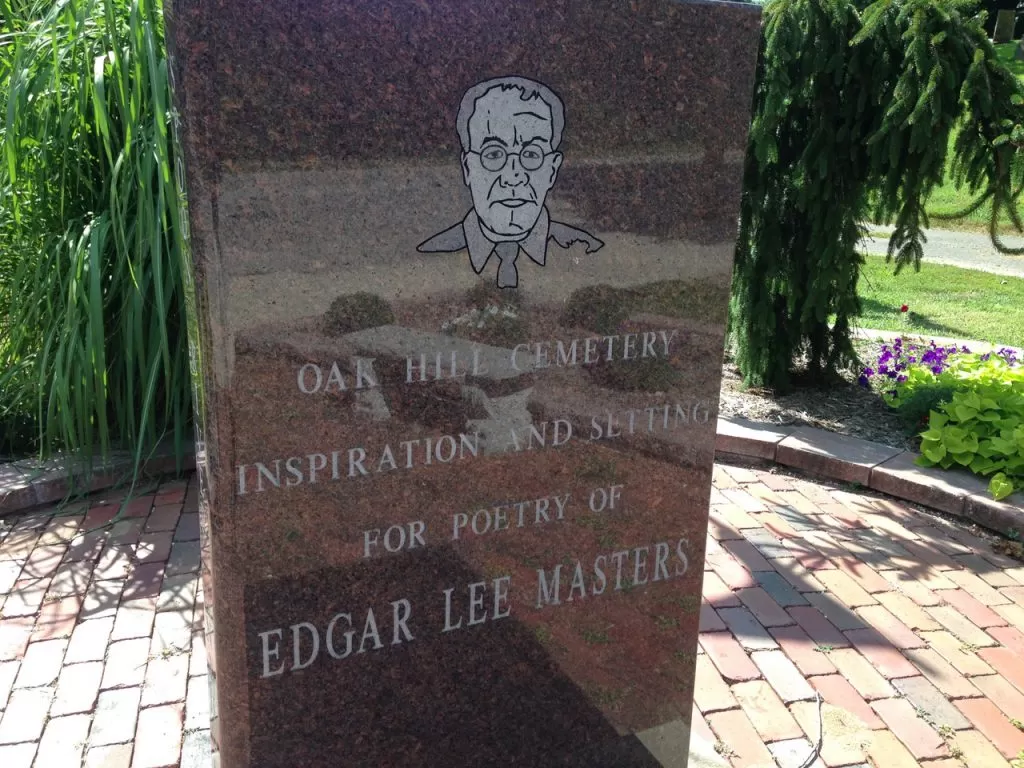

Not far from where I grew up was the town of Lewistown, Illinois, made famous by the poet Edgar Lee Masters, who satirized in verse many of his town’s inhabitants. Many were easily identified by the townspeople and subsequent historians, so I occasionally would roam the hills of Oak Hill Cemetery with my dogeared copy of his 1915 “Spoon River Anthology,” searching for the gravestones matching the subjects of his poems.

Now it seems that whenever I am researching a particular individual, I invariably feel the need to visit their gravesite. I’ve stood beside that of Frank Lloyd Wright in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Gustav Stickley in Syracuse, New York; William Shakespeare in Stratford and John Keats and Percy Shelley in Rome; E.W. Grove in Paris, Tennessee, and Fred L. Seely in Fletcher, North Carolina. More recently I’ve visited the gravesites of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald in Rockville, Maryland, and Thomas Wolfe here in Asheville, each time leaving the traditional pen on their tombstones.

Last week I made a return trip to a nearly forgotten cemetery on a hill overlooking Tryon, North Carolina, where Charlotte Yale and Eleanor Vance, two Arts and Crafts designers, craftswomen, and teachers, were laid to rest in 1954 and 1958. Fifty years earlier they had founded Biltmore Estate Industries, an Arts and Crafts cottage industry which trained young men and women how to make and carve furniture, as well as how to weave homespun cloth on oak looms.

In 1915, the two women left Asheville for Tryon, where they founded Tryon Toymakers and Woodcarvers. Again, they trained young men and women how to make and carve furniture, as well as how to cut and paint brightly colored children’s toys. Always modest about their accomplishments, they shunned attention, even when invited by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to spend a few days with her in Washington.

Charlotte and Eleanor often carved native dogwood blossoms into their walnut and oak bowls, benches, and trays, so it seemed only fitting to leave a vase of dogwood branches at their grave last week. As contradictory as it may seem, visiting them at their gravesites always makes them feel more alive to me.

Until next week,

“Forests may be gorgeous, but there is nothing more alive than a tree growing in a cemetery.” – Andrea Gibson

Bruce