Summer Routes and Family Roots

Growing up on the Illinois prairie with countless other Johnsons and numerous Olsons, Petersons, Andersons, and Swansons, I was familiar with the tragic story of Bishop Hill, a religious commune established in 1846 on 700 acres of land by a group of Swedish immigrants.

They had been led to central Illinois by 42-year-old Eric Jansson, a religious cult leader who, after having denounced all Lutherans, had been forced to flee Sweden. Nearly 1,400 of his followers also left Sweden, but only 400 survived the shipwrecks and cholera which plagued the immigrants. Jansson prohibited his Swedish followers from purchasing their own property, advocating communal ownership of the farms and businesses in Bishop Hill. However, the early years were devastating for the new settlers, as disease, near-starvation, and a series of deadly winters decimated their ranks.

Eric Jansson became embroiled in a bitter custody battle with one of his disgruntled followers who had married Jansson’s cousin. In 1850 the man confronted Jansson inside the county courthouse and shot him to death. Jansson’s murder and some subsequent mishandling of their communal funds prompted the members to dissolve the communal system by 1861.

The commune of Bishop Hill then became the community of Bishop Hill and still exists today, population 128. Its own early obscurity accounts for the existence of several of the early buildings, as no one bothered to tear them down to make room for a Dollar General or a Walmart. Once the historic significance of Bishop Hill was recognized, preservationists began protecting and restoring the structures, many dating back to the 1850s. Four are now owned by the State of Illinois and the community was bestowed National Historic Landmark status in 1984, paving the way for Bishop Hill to become a popular tourist destination.

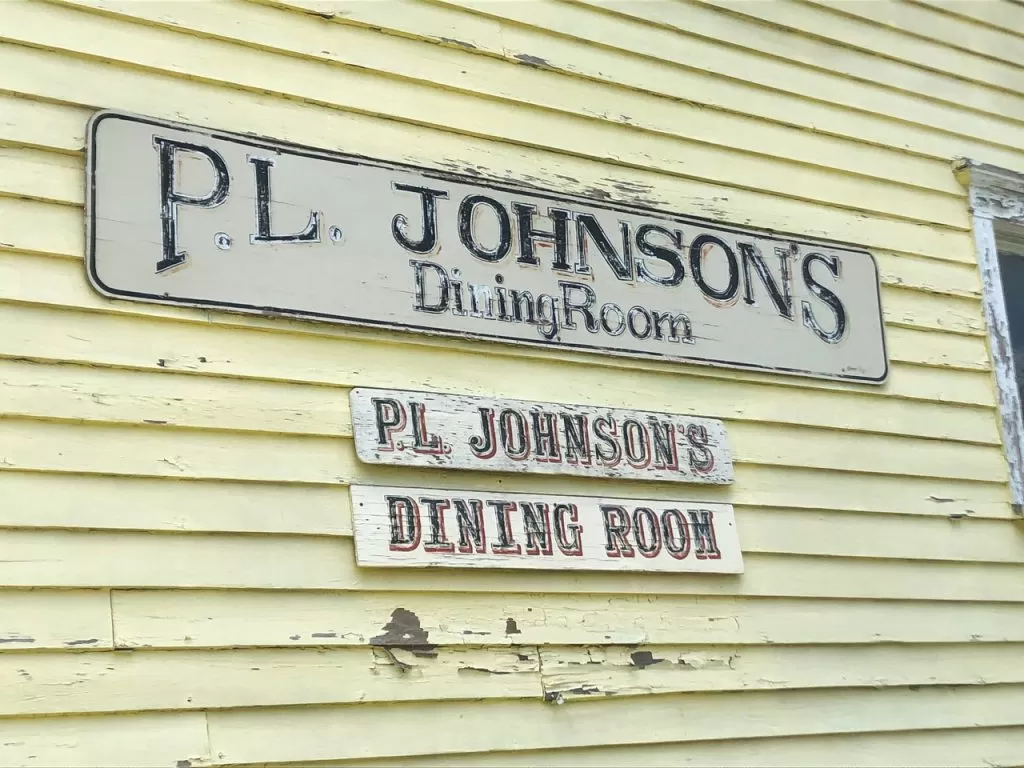

I recently drove to Bishop Hill, arriving shortly before noon on a warm summer’s Friday, just as the townspeople were preparing for two weekend events: the Hummingbird Festival and a Plein Air painting contest. I browsed through a couple of antiques shops, watched a young woman weaving a rag rug on a loom, lingered over an assortment of contemporary pottery, and began studying the menus of the three cafes spaced out along the three-block main street.

I already knew what I wanted to order and knew, too, that all three would have their own version of a traditional Midwestern favorite: Swedish meatballs. I chose a combination bakery and café simply because they had outdoor dining, with tables positioned on a low deck constructed around a large oak tree in the back yard. I lingered over my meatballs nestled on a bed of thick, homemade noodles drizzled with a generous ladle of beef gravy until I was the only diner remaining on the shaded patio.

Five years ago, on my last trip to Bishop Hill, I had brought home a tall Arts and Crafts style vase, and hoped to bring home a memento of this trip as well. Nothing in the shops had caught my eye, though, so I reached for my car keys and had begun planning my return route, when suddenly the oak tree above me dropped a large acorn onto my table. It bounced against my coffee mug and settled atop the waitress’ notepad, as if to say, “Here I am.”

And so, I brought home with me a memento of my latest trip to Bishop Hill, one that will hopefully take root in a vase here in my office and by spring will be ready to plant on our farm, a bit of my Swedish heritage brought back to live in western North Carolina.

Until next week,

“A mighty oak sleeps in a tiny acorn . . . .” – James Allen

Bruce