Taking Virtual Journeys

Until we all begin to feel comfortable traveling again, our computers will have to continue to serve as the gateways to our next adventure. I always look forward to each online catalog published by Brunk Auctions here in Asheville, for they continue to offer a wide selection of quality antiques, just as Bob Brunk had done since he founded the family business in 1983.

As you would expect, the staff at Brunk Auctions has a special sensitivity and advanced knowledge of Southern antiques, along with their reputation for selecting and offering fine Asian, European, and American antiques and art from a variety of genres and eras. Arts and Crafts, as well as 20th century art pottery, is no exception, as they have auctioned exceptional works by all of the Stickley brothers, Charles Rohlfs, Limbert, Newcomb College, Roycroft, Rookwood, Heintz, and others.

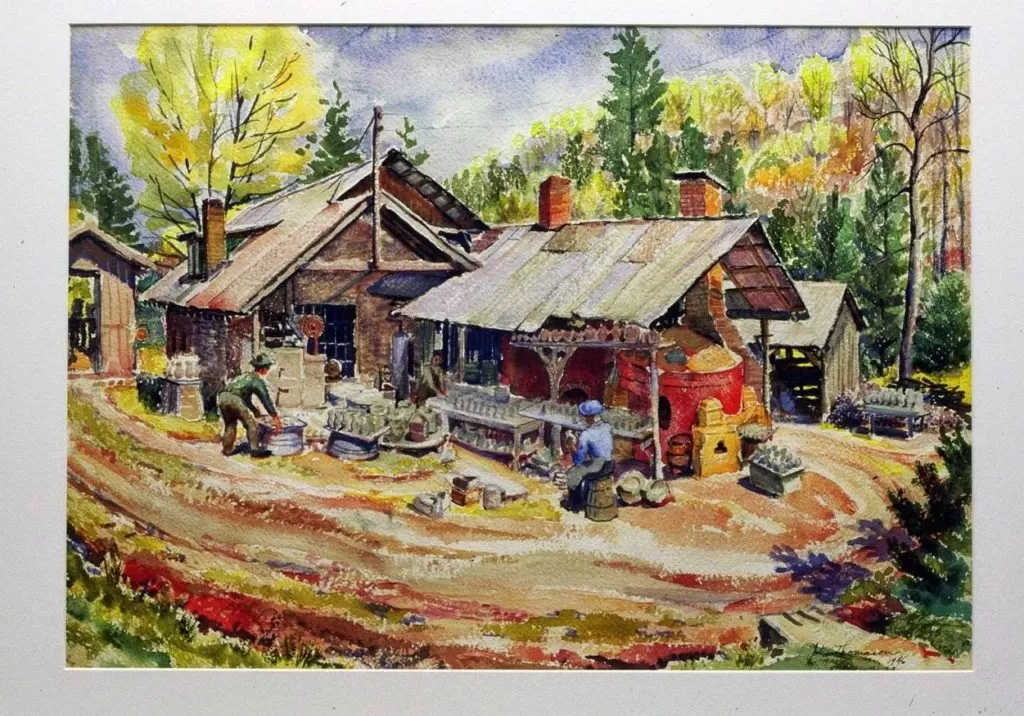

Their April 9-10 auctions will include an array of art pottery created by Walter Stephen, founder of Pisgah Forest Pottery outside Asheville. Located in a lush, narrow valley bisected by an idyllic, tumbling brook, Walter Stephen set up his pottery, kiln, and showroom in a few small sheds alongside a busy highway leading into Asheville. Some are still standing.

There beginning in the 1920s the self-taught potter mixed his own clay, turned his own vases, and experimented with a variety of glazes on what became known as Pisgah Forest Pottery. Most of his wares were sold to tourists attracted to the quaint roadside pottery.

Walter Stephen is best known today for two types of decorated art pottery. Using a small, pointed brush, he meticulously applied layer upon layer of liquid clay upon the vase, creating scenes inspired by Appalachian mountain lore. In contrast, he also developed a crystalline glaze, wherein glassy starbursts appear like frost crystals around the vase. Both have become highly collectible today.

What I am always struck by when looking at the pottery of Walter Stephen and others like him, including the more famous George Ohr, is that rather than aspiring to factory production, Southern craftsmen and craftswomen of the early twentieth century favored individual expressions, often inspired by their rural environment.

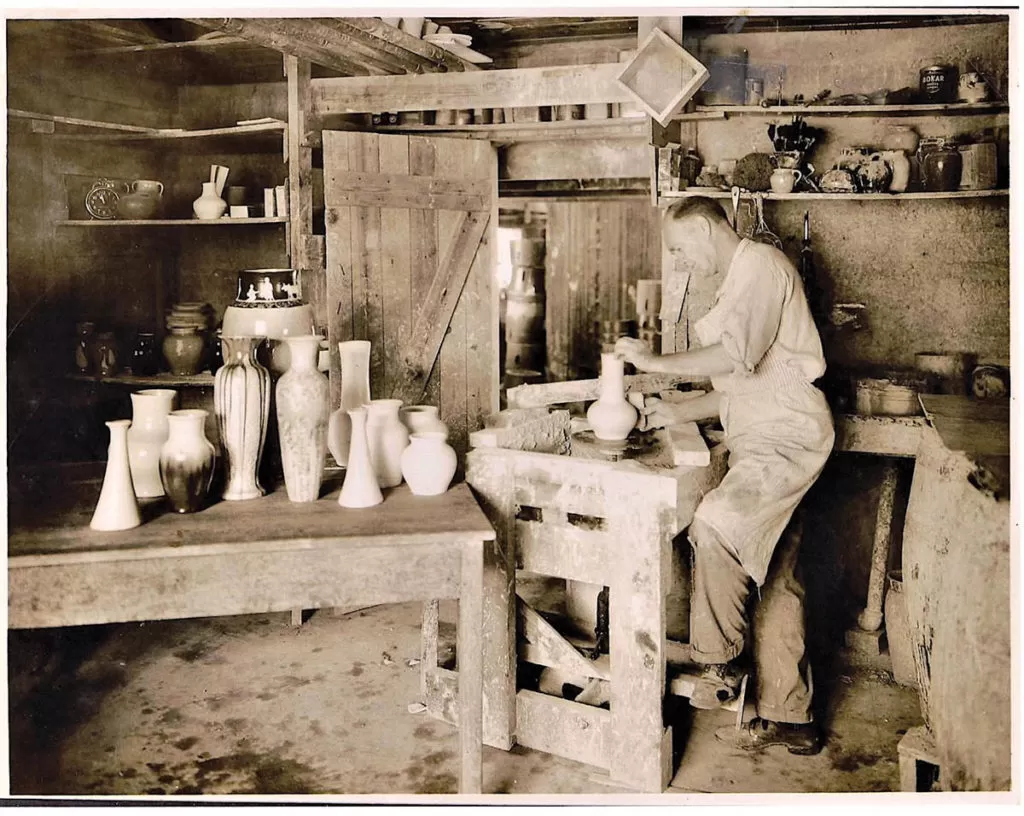

While Arts and Crafts practitioners in other parts of the United States rejected the British reformers call for allowing a single craftsman to take the process of creation from the initial design to the finished product as being too impractical, in the South it was often a necessity. A solitary potter like Walter Stephen would dig his own clay, haul it back to his shop, grind and mix it to the proper consistency, turn the shape on his treadle wheel, apply the glaze he had ground, and fire it in his kiln – not because he had read that Professor John Ruskin over in England had advised it, but because if he didn’t, he wouldn’t have any jugs, crocks, vases, or jars for his family to use, sell, or trade.

As a result, Pisgah Forest Pottery is not as polished nor as sophisticated as molded Rookwood, Weller, or Van Briggle pottery, but it actually comes closer than any of them to adhering to the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Until next week,

“An artist who works with his hands, his head, and his heart at the same time creates a masterpiece.” ― Amit Kalantri

Bruce

PS – In case you missed seeing Bruce Johnson’s seminar “From Mountain Crafts to Southern Arts and Crafts” during last February’s virtual 34th National Arts and Crafts Conference, you can view it here: