The Forgotten Brother

Publisher Peter Copeland of the Parchment Press was correct when he wrote, “If Gustav Stickley was considered ‘the forgotten rebel,’ surely Charles Stickley is ‘the forgotten brother.’”

Born in 1860, four years after Gustav, Charles Stickley also trained in their uncle’s chair factory as a teenager, helping to support their mother, two sisters, and three younger brothers – Albert, Leopold, and John. By 1883 all five Stickley brothers were well on their way to careers in the furniture industry. Their first venture, aptly named Stickley Brothers and Company, proved two points: the five Stickley brothers were each capable of building and directing successful furniture companies, but incapable of all working closely together.

By 1904, Gustav had broken away to form Craftsman Workshops. Albert had moved to Grand Rapids, taking the name Stickley Brothers Company with him. Leopold and John George had started L. & J.G. Stickley; and Charles had become a partner with a family friend Schuyler Brandt, whose major contribution to the partnership may have been his financial investment. Their firm was named the Stickley & Brandt Chair Company. While the company name appeared on a decal shopmark, it was the inclusion of the script signature “Chas. Stickley” that reflected the leading role Charles played in the company.

Ironically, it was not until 1909 that Charles Stickley introduced his first line of Arts and Crafts furniture. Prior to then, Stickley & Brandt had built a successful business mass-producing fancy chairs, rockers, and settees in various Victorian styles. Their extensive 1909 catalog was entitled “Modern Craft Styles by Chas. Stickley” and has since been reproduced by Peter and Janet Copeland and their Parchment Press. The catalog generated headlines and major news stories in the furniture press, along with a few caustic observations by his older brother. As Gustav declared in his own 1909 catalog, “To add to the confusion, some of my most persistent of these imitators bear the same name as myself….”

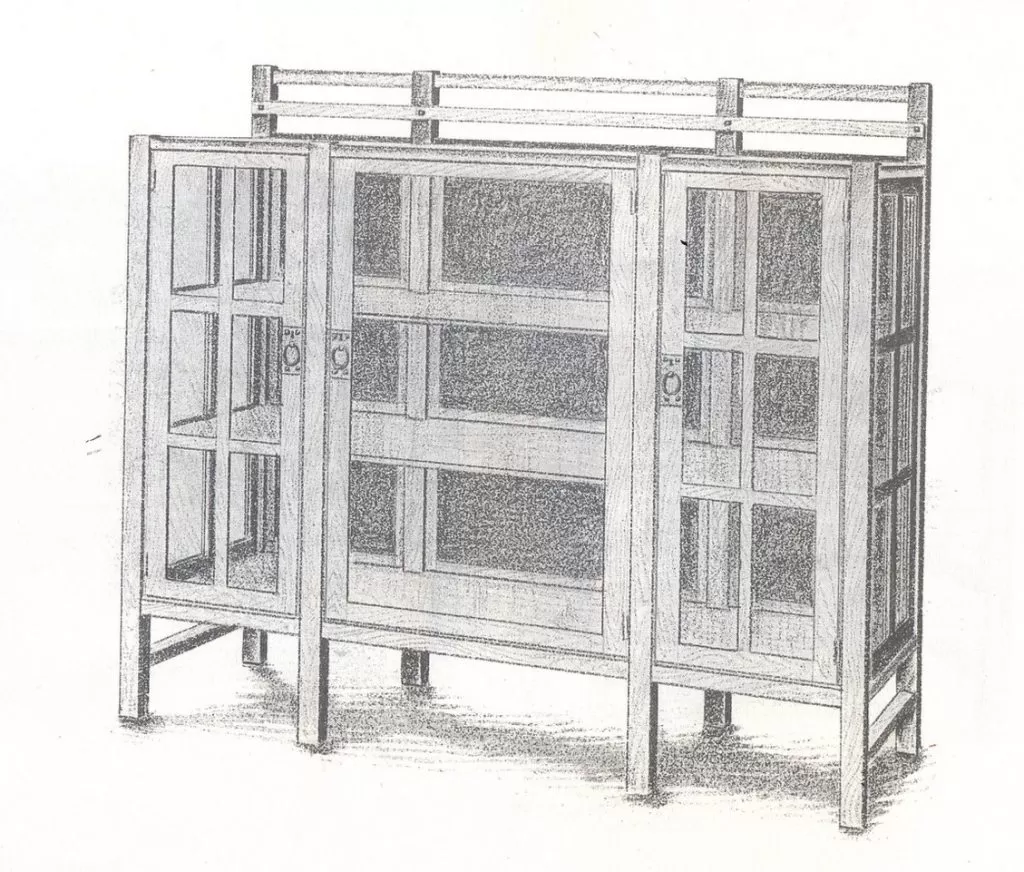

And Charles was an imitator, selecting the more successful pieces from both the Craftsman Workshops’ line and that of L. & J.G. Stickley for his factory craftsmen to produce: settles, chairs, desks, sideboards, bookcases, and china cabinets. And while his brothers may have been irritated, none sued their brother for any act of infringement. In fact, it is believed that Gustav provided Charles with door hardware for his china cabinets and bookcases, something which has caused a degree of confusion among collectors today.

Several years ago, I was caught off guard in a Tryon, NC antiques shop when I spotted Gustav Stickley hardware on a three-door china cabinet that, while well-designed and expertly constructed, was certainly not from the Craftsman Workshops. The piece was unsigned, so I returned home without it and started doing my research. Toward the back of the reprinted 1909 Charles Stickley catalog I had ordered from Parchment Press, I found it illustrated: model #1915, an original Charles Stickley-designed china cabinet bearing door hardware from Craftsman Workshops.

Needless to say, I made a quick trip back to Tryon.

I learned several lessons that day and other days similar to it, including the value of the reprint catalogs available to us. They have been reprinted largely through the efforts of the late Stephen Gray and those currently of Peter and Janet Copeland, who started Parchment Press and then took over Turn of the Century Publications from Stephen. These catalogs are critical in explaining the numerous discrepancies we encounter, especially when we rely too heavily on hardware and shopmarks to identify the maker and the year of production.

Until next week,

“Get to know the furniture first by examining it carefully, then look for marks as confirmation.” – David Cathers, author of “Furniture of the American Arts and Crafts Movement”

Bruce

PS – To see what you might be missing on your research bookshelf, go to: https://turnofthecenturyeditions.com/