The Visions of Harry Clarke

by Kate Nixon

(Editor’s note: this article has been republished. The original date of publication is September 30th, 2022.)

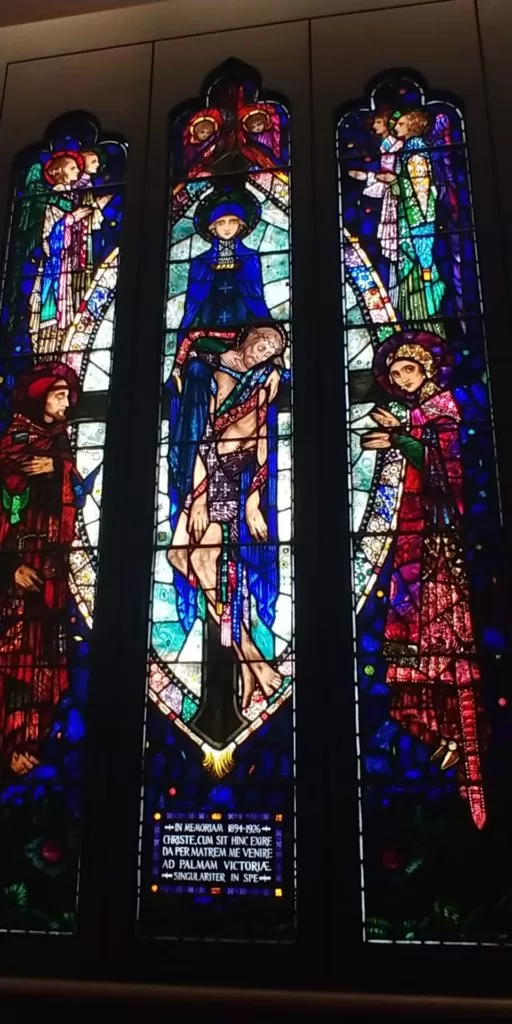

“The Mother of Sorrows”, designed by Harry Clarke ca. 1926. The window was designed as a First World War memorial for Dowanhill Training College in Glasgow, but became instead a memorial to Sister Superior Mary of Saint Wilfred, who had commissioned it. It now resides in the National Gallery of Ireland. Photo courtesy of Kate Nixon.

Harry Clarke. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most well-known figures of the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement, Harry Clarke’s contributions were not only to both Catholic and Protestant churches, illustrations in famous publications, and his iconic windows featured in museums: his aesthetics were perfectly representative of a traditional culture in his projections of Catholic figures, a demand to return to native Irish imagery. His professional career was encapsulated during the period of Irish history known as the emergence of the Free State. During a time when the national identity of Ireland was unclear, his works and the works of other artisans and craftsmen presented a clear preference for the traditional and the simplicity of natural beauty. Today, Clarke’s windows are located all over Ireland, the United Kingdom, and in one special case, at the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, Florida. One blogger put it simply: “The windows of Harry Clarke are like jewels, strung out across Ireland.”

From his customized stained glass windows in the Honan Chapel in Cork to a collection in Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery to an entire room at the National Gallery of Ireland dedicated to his works, Clarke was a key stained glass artist whose works were easily accessible in said churches and museums. While in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, my mother and I were ushered into a blackened room, waiting to view the Frederic William Burton painting (one of her favorite paintings ever) “The Meeting on the Stairs.” The dark room was lit with the brilliant hues of his works; I loved the deep hues of blues and reds that were among many windows in the room with a romantic but gothic glow. The dominating and massive window in the room, “The Mother of Sorrows” held my gaze for what seemed like forever. Among the many talents of Clarke was his ability to create the faces of his subjects; you can’t help but see the sorrow in Mary’s eyes.

A stained glass panel designed by Harry Clarke located in the Honan Chapel in Cork. Photo courtesy of Kate Nixon.

During my time spent in Ireland, my sisters and I enjoyed a drive to the city of Cork by a young historian and author with a missive of revealing the significance of Cork City as both a cultural capital and home to the rebellious in Irish history. One requested stop on the tour was the University of College Cork, where the Honan Chapel is located. For those readers who own the publication The Irish Arts and Crafts Movement: Making It Irish, the accompaniment to the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College exhibit of 2016, it’s widely known that the chapel was a massive win for the local supporters of the movement. The Honan Chapel is a catholic church built with features similar to the Romanesque revival style, designed by solicitor John O’Connell, another member of the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement and executor to Isabella Honan, the financial donor to the Chapel. As contributing writer Ann Wilson wrote in the publication Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State, the design of this church was indeed unique. “The Honan Hostel Chapel is unusual in many respects for an Irish Catholic Church of the period, not least because important decisions on design and decoration, were made not by diocesan bishops and priests which was almost always the case in other churches, but by a layman with strong connections to the Arts & Crafts movement, a Dublin solicitor, John O’Connell.*”

I walked inside the chapel and immediately saw Harry Clarke’s contribution: eleven of nineteen stained glass panels showing Irish saints along with imagery of Jesus, Mary, St. Joseph and St. John. The vibrant colors, the impressive details and the facial expressions on these panels put Harry Clarke’s talents on the cultural map in 1915, which came along during a time when Catholic institutions were open to regulation by the Vatican influence. These windows were a vibrant visual, showing figures in Catholicism and Irish mysticism. In the image above, note the impressive tones of blues and reds pervasive in the window in addition to the influence of the natural, woven in the glass art in the form of leaves. Stained glass art should leave parishioners with a sense of inspiration – and it absolutely worked well here.

One of eight panels of the Geneva Window: this panel depicts the work of James Joyce and Seumas O’Kelly. Clarke unfortunately passed away before he could see his finished result installed elsewhere: the controversial nature of the window resulted in a rejection from its intended location: the International Labor Building in Geneva. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, the celebrated Harry Clarke wasn’t just known in Europe. It wasn’t until I was back home that I realized that the creator of said stained glass artwork and the creator of the famous Geneva Window were one in the same. Currently residing at the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, Florida, Harry Clarke’s last creation was the Geneva Window, an eight-panel work of art depicting the creations of 15 Irish authors ranging from Lady Gregory to G.B. Shaw to W.B. Yeats (who helped Clarke pick out the authors as well) to James Joyce. While the window was initially a commissioned work from the Irish free state in 1926 to celebrate its newfound independence and be installed in the International Labor Building in Geneva, the window ultimately became the subject of controversy as the depiction of the scantily-clad maidens in one of the panels was considered too inappropriate. Among the other offending themes within this artwork: the presence of liquor, the inclusion of the divisive author James Joyce, and the protestant influence (as some of the depicted authors were indeed protestant.)

While Clarke’s health was unfortunately failing, Clarke continued to inquire about the window, but to no avail. The suggested meetings to talk about potential alternatives never took place. The powers that be ultimately rejected the iconic window, which was devastating to Clarke. Clarke soon passed away, never knowing what happened to his Geneva window. We, however, do know the final resting place: the window was eventually sold to art collector Mitchell Wolfson and now has a permanent home in the Wolfsonian.

When I eventually make my way down to Florida, you’d better believe I’ll be stopping at the Wolfsonian to view the extraordinary Geneva window and pay tribute to both the authors of Ireland, but the vision of celebrated artist Harry Clarke.

You can view the Geneva Window virtually here.

* excerpt from the publication Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State, edited by Angela Griffith, Marguerite Helmers, and Roisin Kennedy.