When Is a Shopmark Not a Shopmark?

This article has been re-published. Original date of publication: June 18th, 2019.

When is a Shopmark Not a Shopmark?

Perhaps when it’s a signature?

I’ve had a fascination with Arts and Crafts shopmarks ever since I spotted my first red Stickley decal on the rung of a Craftsman Workshops dining room chair. I was standing in the parking lot outside my first antique restoration shop in Iowa City when Jim Mall, an antiques dealer from Chicago, pulled up in a pickup truck literally loaded with Arts and Crafts furniture. The year was 1979 and Jim periodically made a trip out through Illinois and Iowa, scooping up Arts and Crafts furniture for his savvy Chicago clients.

In 1981, author David Cathers was the first to undertake a serious study of Gustav Stickley’s furniture and the evolution of the various shopmarks which Gustav used from 1901-1916. We still rely on his book “Furniture of the American Arts and Crafts Movement” not only to help us determine the possible years associated with a particular style of shopmark, but to remember David’s advice: “get to know the furniture first by examining it carefully – then look for marks as confirmation.”

In late 1901 Gustave (he dropped the “e” in 1903) severed his contract to produce Arts and Crafts furniture for the Tobey Furniture Company and began marketing his own line of Craftsman Furniture, relying on his new monthly publication “The Craftsman” to bring it to the attention of homeowners across the country. It was not until January of 1902, however, that Stickley settled on a prominent shopmark: the red joiner’s compass over the name “Stickley.”

How, then, were those pieces made in the fall and early winter of 1901 marked?

For starters, many of them were not. Gustave may not have felt it necessary to distinguish his earliest 1901 Arts and Crafts furniture from that of his competitors, including some of his brothers. That changed in 1902, however, as the style grew in popularity and several more firms began introducing new lines of similar furniture.

In the fall of 1901 Gustave may have experimented with different shopmarks, some of which may have proved too fragile to survive more than a few decades or so. Other shopmarks could have been erased during the refinishing craze that started in the 1960s, at a time when Arts and Crafts furniture was often deemed “Mission Joke.”

Gustav Stickley (1858-1942) single-door china cabinet. Photo courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers.

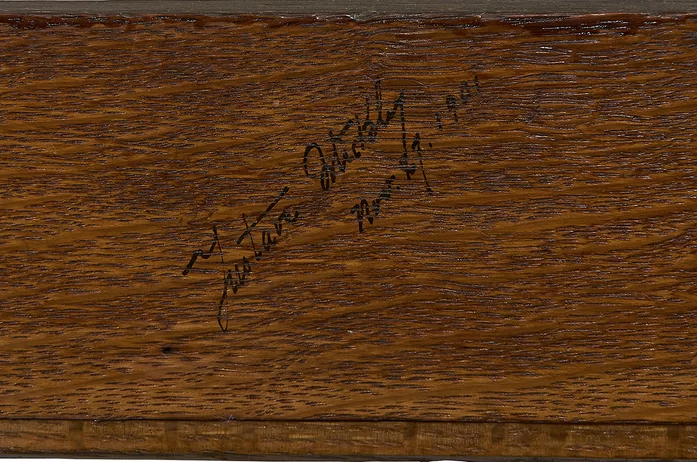

On November 27, 1901, someone in the Eastwood, New York, factory of Craftsman Workshops did experiment with a possible shopmark on the back of a single door china cabinet. Written in ink is the scrawled signature “Gustave Stickley” and the date “Nov. 27, 1901.”

Signature “Gustave Stickley – Nov 27, 1901” Photo courtesy of Toomey & Co. Auctioneers.

The china cabinet surfaced in the June 9 auction of Toomey & Co. in Oak Park, Illinois. The consensus of those who inspected the china cabinet was that there was no doubt that (1.) the china cabinet was constructed in the Craftsman Workshops in 1901, and that (2.) the signature appeared to be original to the piece.

Who, then, signed it?

The order for the date and signature undoubtedly would have come from the boss, but did Gustave instruct someone in the shop to sign his name and the date to this one china cabinet?

Or did Gus, for whatever reason, come out of his office into the workshop that Wednesday in November, pick up a fountain pen, and decide to experiment with signing and dating it himself?

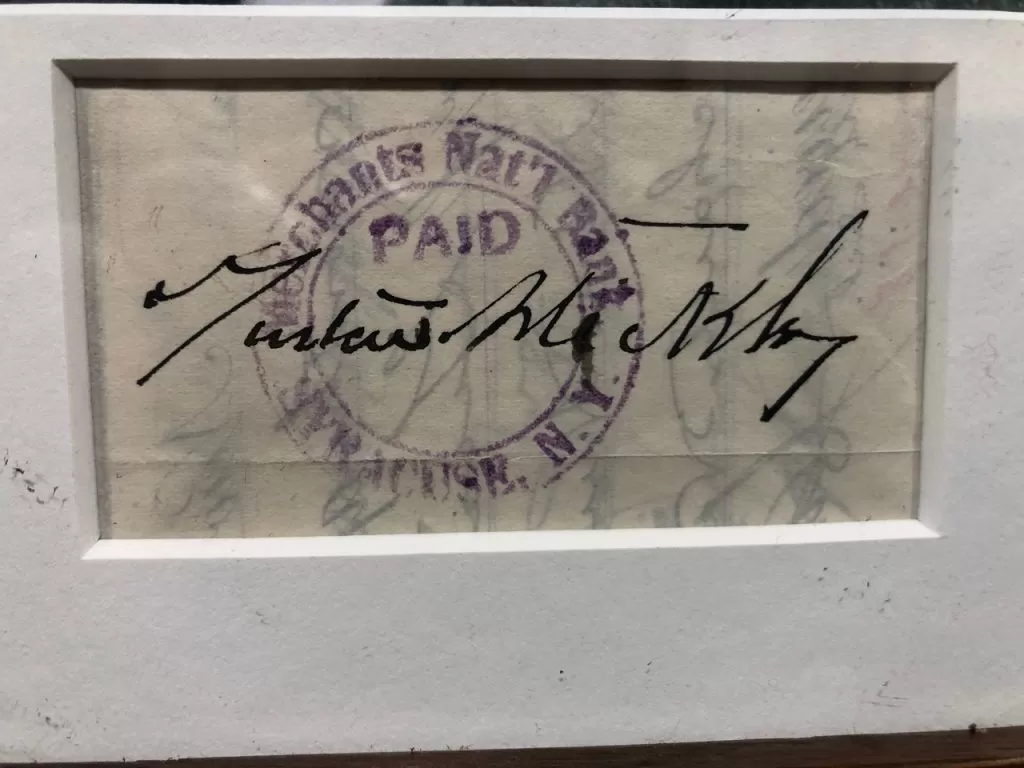

We have very few authentic original signatures by Gustav Stickley to be able to make a definitive comparison between the signatures. And as any autograph expert will attest, signing your name to a board on the vertical back of a large piece of furniture is not going to look the same as when you sign a legal document sitting at your desk.

It seems we will never know whether or not this 1901 Craftsman Workshops china cabinet bears a rare “Gustave Stickley” personal signature, but it is invigorating to know that mysteries can still emerge — to keep us thinking, debating, and smiling at ourselves and our obsessions.

Until next week,

The ball-point pen was introduced in 1938. (I had to look that up.)

Bruce