Working Up My Grief: What Does “Arts & Crafts” Do For Us In Times of Loss?

by Kate Nixon

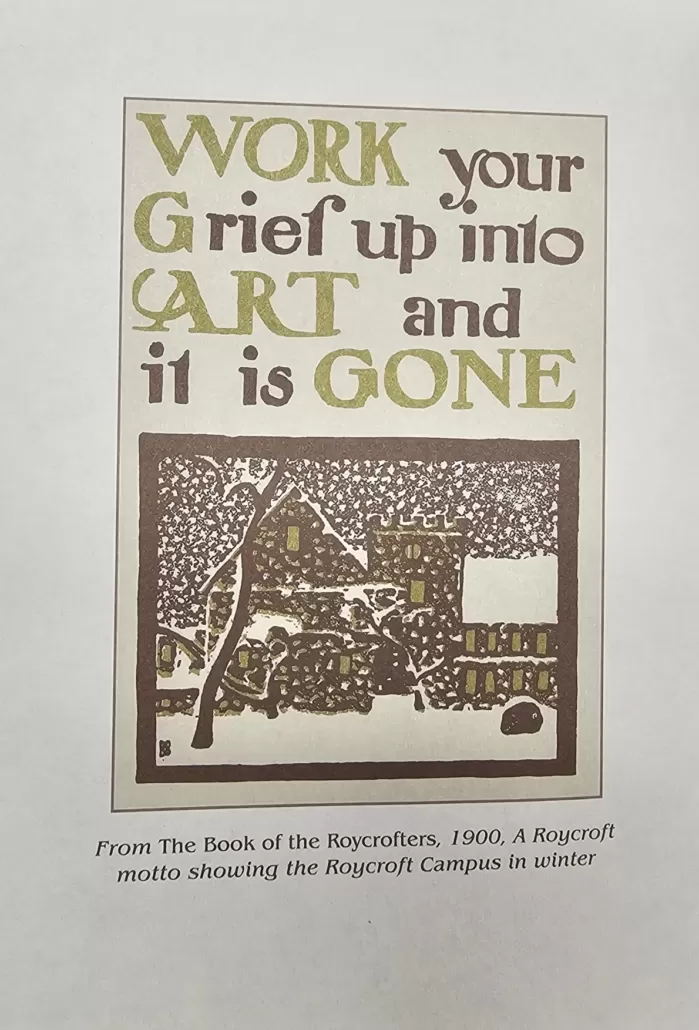

“Work Your Grief Up Into Art and It Is Gone.”

The very first page of Arts & Crafts Ideals: Wisdom from the Arts & Crafts Movement in America – one of my first Arts and Crafts books – is a reminder from The Book of the Roycrofters. Those words were paired with the woodblock printed image of the iconic Roycroft Campus covered in white snow. When I started to tell folks of my recent loss, some of the first words out of their mouths would be that quote. While I fully agree with this statement and consider myself someone with enough creative skill to keep myself engaged in the arts, I continue to look at a half-finished painting – a canvas propped up in my bedroom – in the times where I am mentally fatigued and temporarily without positivity to fathom continuing with it. At least not now.

A screenshot of the first page of Arts & Crafts Ideals: Wisdom for the Arts & Crafts Movement in America, a book of passages compiled by Bruce Smith, Yoshiko Yamamoto, and Gail Yngve.

My father died suddenly at the age of 71 earlier this month. It was December 7th to be exact – a day already living in infamy. If you were at the 36th National Arts & Crafts Conference and Shows earlier in February of this past year, you probably saw him as a tall man – calm and with a smile and always with a calculator looking at invoices. Anyone who has lost a parent knows how sorrowful and devastating it is. As a country, we’ve already lost so many souls in the past three years that our minds have become numb to someone passing away and an RIP passage is already queued up in our minds. And yet when it hits home, it digs deep right into head and heart.

There are many studies exploring the therapeutic value of creating art as a means of healing. One such exploration at the National Arts & Crafts Conference at the Grove Park Inn’s seminars exploring its effect on mental health, tough times, and in some cases, extreme duress was 2020’s “Beating Swords Into Ploughshares: World War I and the Arts & Crafts Movement “by Ryan Berley about soldiers creating in the trenches. Another example: the well known art pottery firm Marblehead Pottery was started as part of a therapeutic program back in 1905 at a clinic for women suffering from nervousness disorders. In that case, pottery turned out to be most effective for the turn of the century program’s participants and thus it was the start of a pottery firm whose works would fill the best Arts & Crafts collections in the country today.

But what does the movement teach those who don’t have a creative bone in their body? What does the movement say to people who don’t have the creative juice flowing?

Revisiting the Natural

The idea of appreciating a harmonious space with its beauty and simple design seems far fetched when you’ve lost a loved one. Your vision can quickly go from vibrant to muted as you mourn. However, a reminder of the beauty of the natural is the most obvious choice of what the movement can give. Whether you are a seasoned artist or someone whose creativity is limited to drawing stick figures, we all know a walk outdoors in the fresh air is inherently healthy and universally good for the soul. But delving back into the movement, a major ideal that those new to the Arts and Crafts movement are immediately struck with is when beautiful objects built as a reminder of the natural are paired with solid and straightforward design of a room’s decoration is not only pleasing to the eye, it can offer a cozy and comforting space. Maybe not a large, bright and white space, but a cozy and warm space. Despite all we do in modern society to create bigger, better, stronger – all we really need is the uncomplicated, something to make us smile and something to remind us of what the natural elements of earth can give to us.

Sunrise over the Log House on the grounds of The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms. Photo Courtesy of Vonda Givens.

Community

“It hopes to to bring designers and workmen into mutually helpful relations, and to encourage workmen to execute designs of their own.” – Herbert Broadfield Warren, secretary of The Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston, Mass. Fall 1898. (Smith, Yamamoto, and Ingve, p.50)

The examples of guilds and communities created in the early American Arts and Crafts Movement are endless. The Roycrofters of East Aurora, New York (whose efforts populated the interiors of the Grove Park Inn), the Arts and Crafts colony of Elverhoj in New York, the Rose Valley Colony of Rose Valley, PA, the Byrdcliffe colony of the Catskill Mountains, Village Industries at Deerfield, the Arts & Crafts societies found in any of America’s larger cities, and all the John Ruskin and William Morris influenced guilds found in Europe – all are founded of the Arts & Crafts philosophies and all emphasizing the importance of community. One such group in Boston, Mass., The Society of Arts and Crafts established in 1897, was created in the words of the society’s secretary Herbert Broadfield Warren, for “the purpose of promoting artistic work in branches of handicraft. It hopes to to bring designers and workmen into mutually helpful relations, and to encourage workmen to execute designs of their own.” (Smith, Yamamoto, and Ingve, p.50) While a number of these guilds still exist today including The Roycrofters At Large Association, The Arts and Craftsmen Guild, and Boston’s own The Society of Arts and Crafts, and so many others across the country, it is a reminder that we cannot grow as artists and people without our fellow man guiding us. When the feeling might occur to withdraw from society, this movement says: Don’t. A main principle of Handicraft after all refers to both designers and workmen working together and teaching each other to grow both professionally and personally.

The examples of guilds and communities created in the early American Arts and Crafts Movement are endless. The Roycrofters of East Aurora, New York (whose efforts populated the interiors of the Grove Park Inn), the Arts and Crafts colony of Elverhoj in New York, the Rose Valley Colony of Rose Valley, PA, the Byrdcliffe colony of the Catskill Mountains, Village Industries at Deerfield, the Arts & Crafts societies found in any of America’s larger cities, and all the John Ruskin and William Morris influenced guilds found in Europe – all are founded of the Arts & Crafts philosophies and all emphasizing the importance of community. One such group in Boston, Mass., The Society of Arts and Crafts established in 1897, was created in the words of the society’s secretary Herbert Broadfield Warren, for “the purpose of promoting artistic work in branches of handicraft. It hopes to to bring designers and workmen into mutually helpful relations, and to encourage workmen to execute designs of their own.” (Smith, Yamamoto, and Ingve, p.50) While a number of these guilds still exist today including The Roycrofters At Large Association, The Arts and Craftsmen Guild, and Boston’s own The Society of Arts and Crafts, and so many others across the country, it is a reminder that we cannot grow as artists and people without our fellow man guiding us. When the feeling might occur to withdraw from society, this movement says: Don’t. A main principle of Handicraft after all refers to both designers and workmen working together and teaching each other to grow both professionally and personally.

Back to loss: as I tell people, I am all of a sudden surrounded by people who have lost a loved one recently. The receptionist who takes my office rent? She lost her father this year. The therapist who works in my building? Lost her own father last month. My neighbor? He lost his partner to cancer last year, but the pain is still as fresh as ever. We exchange stories on the after life processes – social security filings, organizing accounts, hiring an estate planning attorney, tips when telling the extended family about your loss. There are so many things we don’t think about when we are in mourning, but there is a laundry list of things to do. A list that becomes realized the more you talk to others. It’s not just about the exchange of information though — every single one of those people mentioned gave me a hug without thinking twice. The heartfelt connection you feel with each person you talk to who has loved and lost helps heal a little bit of that broken heart. Everyone knows what it’s like to lose someone, so don’t think you’re completely alone because you aren’t. You’re part of a club that no one asks for, but it’s there and massive.

Embracing Work and Education

According to Elbert Hubbard’s philosophies, found in his own 1930 publication The Philosophy of Elbert Hubbard, “Education comes through doing things, making things, going through things, taking care of yourself, talking about things.” At Hubbard’s own Roycroft Campus, Hubbard was able to market and become one of the most well known icons of the American Arts & Crafts Movement as he brought talented craftspeople together to make the books, furniture, metalwork, lighting, china, and so many other genres of Roycroft works – and he organized weekly lectures, concerts, evening classes, piano lessons, etc to his own workers and the visitors to the campus. He knew that the Head, Heart and Hand philosophy was key to not only individual health, but beneficial to the whole community. That same philosophy was found in Boston’s own Saturday Evening Girls Club/Paul Revere Pottery, where the early days of the club saw these girls who joined this pottery firm treated to presentations, music and performances, a gift to these women who were newfound citizens of America without knowing a single soul.

In times when the heart is aching, work can be helpful to keep the mind going. Writing and organizing a conference and shows certainly keeps my mind churning away until my vision is realized in February. With the Arts and Crafts movement, work was incredibly important to keep up that Head, Heart and Hand philosophy. And while the relationship between artist and machine has been a tricky one in the early 20th century and has only grown more complicated in recent times, the achievements of the human hand were well documented in the publications dedicated to the decorative arts, much like this description of a Grueby lamp by C. Howard Walker in a March 1900 issue of Keramic Studio.

“Instead of the mechanical formality which has so often been mistaken for precision, every surface and line of this ware evinces the appreciative touch of the artist’s hand… Both in concept and design, in glaze and color, each piece of the Grueby ware is individual and of unusual merit and deserves to take a prominent place amongst the best known wares.” – C. Howard Walker, Keramic Studio, March 1900 (Smith, Yamamoto, and Ingve, p.14)

I was lucky to have my father for the years that I did. I’m also lucky that I can hear his calm advice in the quiet moments at night. Finally, I’m lucky that in working last year’s conference, Dad fully understood what it was about and why I and my staff work so hard all year for a three-day celebration in February.

For those of you who have signed up for the 37th National Arts and Crafts Conference and Shows in Asheville, you’ll see me there. Hands ready to work, Head ready to solve problems, Heart a little worse for wear, but still here and ready to connect.